- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

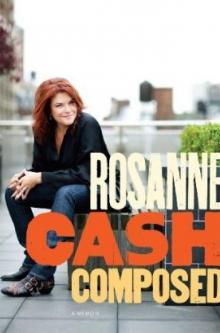

Composed Page 5

Composed Read online

Page 5

I turned twenty-one while I was in London but thought it cool and grown-up not to let anyone know. For that weekend I arranged to go to Scotland with some of the people from CBS to stay at the huge manor house of one of our artists, a country singer who also worked the oil rigs in the North Sea. His wife, who was from the American South, made cornbread and black-eyed peas for dinner, dished out with a thick regional accent. Beginning to miss my mother, with whom I had not lived since the day after I graduated from high school, I decided to tell a few people it was my birthday, and they came up with a cake for me. I lay awake a long time in a small guest bedroom that night, thinking of my mother, my sisters, my father, and the fact that no one in my family was there to witness my turning into an adult.

I saw a lot of bands play in London, including a reunion concert of the Small Faces, which I went to alone. Some sort of reception was held after the show, which I attended mostly because a free buffet was promised. (Under normal circumstances, an evening meal was nonexistent for me unless someone took me out.) At around one a.m. I suddenly found myself in a near-deserted basement room with a pillaged buffet table and not a soul I knew anywhere around. I had counted on getting a ride home from David or Anthea, as I thought they would surely be at the show and the reception, or from someone else I knew who had a car or a bit of money, as I did not have a penny on me. I panicked for a moment, not knowing how I would get home, and I realized that I had no choice but to walk the few miles to Hampstead in the freezing early hours. I gathered my thoughts into a singular point. I banished my fear of being alone on the streets in the middle of the night. I did not allow any other possibility to enter my mind other than a long trudge and a safe arrival. I set out in my very high-heeled boots and marched myself up through Piccadilly, on through Camden Town and Mornington Crescent, up Hampstead Road and along to No. 3 Carlingford Road. It was bitterly cold, and I was tortured by my ill-advised footwear. My entire body screaming in protest, I kept my eyes forward and my anxiety under wraps, and arrived home at around four a.m., where I fell immediately into bed. That walk was the dividing line in my life, marking the boundary between my former unformed, raw, swollen personality and the more emotionally sinuous, urbane girl I became. There would be periods in my future when the old girl would take possession of me for a few weeks or months, but from then on I had the blueprint, devised on the long walk, and the determination, also inaugurated in those few hours, to escape from the inundation of her dark, turgid spirit.

In the early summer of 1976 I went home to Nashville for a brief visit. The first thing my dad announced after greeting me was, “That’s enough. You need to stay home now. You need to move back to the United States.” I was stunned. He did not say this in a pleading or coercive way, but simply delivered it as an edict. I did not even think to argue with him, his effect was so forceful, but I made a feeble remark about having to go back and pick up my belongings. He dismissed this instantly. He told me to have my girlfriends pack my trunk, and to deal with terminating my sublease by long distance. I called Brenda, who I had gradually grown closer to than Sandy over the past few months, and she and Sandy packed up my trunk with my clothes and records and antique dishes, and shipped it to Nashville. I called Derek and told him I wasn’t coming back. I called the real estate agent and told him I was vacating the flat. I applied to Vanderbilt University for the coming September, found out I was lacking a math credit, and hired a private tutor to teach me trigonometry. I realized much later that Dad was afraid I would disappear from his life; that I would become a permanent expatriate and lose touch with my family and my roots. He told me years later that he had a fear that I would be lost to them forever if I stayed in Europe any longer. He was probably right.

Brenda came to see me in Nashville late that summer. As we sat by the pool at Dad’s house on the lake, I was miserable, hating her for being so beautiful when I was bloated with hormones, hating her for having a return ticket to London. It had not even occurred to me—and it wouldn’t occur to me for another twenty years—that I could have argued with my father and simply gone back. It seemed a bad moment for my old, limp personality to resurface, but in retrospect, I’m grateful he could see the possible trajectories of my life, and intervened to keep me connected to him and the rest of my family.

“We found your journal when we were packing your trunk,” Brenda suddenly declared. “Sandy started to read it aloud, but I told her it was wrong, that we shouldn’t read it and she should stop, because you were so lonely.” She looked at me steadily. “You were so lonely,” she said again, almost accusingly.

I hated her for knowing more about me than I knew about myself.

The next time I saw her, several years later, she and Sandy were both living in New York. I spent one wild weekend with them there, and they tried to set me up with a young man who told me confidentially that he was considering the priesthood. We went to a lot of clubs and parties and ended up at the Green Kitchen, in Hell’s Kitchen, at five a.m. on a Monday. I crawled back to my tiny room at the Berkshire Hotel later that morning, deeply depressed, and went back to Nashville the following day. I saw Brenda a few more times, once after she married the actor Corbin Bernsen, when they were driving to Los Angeles, but eventually lost touch with both sisters.

That September I entered Vanderbilt, and with my year’s worth of credits I managed to take mostly sophomore classes, trying to fit myself into a program where I was already two or three years older than my classmates. I was not only older, however, but far more experienced, not to mention eccentric, than the other students. I had no interest in the social aspects of college, which made it impossible for me to feel a part of the community, and I don’t think I spoke more than ten words a day for the entire academic year. I liked my studies, particularly a creative writing class, which was taught by Walter Sullivan, a brilliant writer himself, and while I found a mild sense of camaraderie there, I still made no real friends.

A few months into the school year I moved out of my dad’s house, having found an apartment on Seventeenth Avenue South, at the back of an old building (which, ironically, I would buy six years later when I was married to Rodney Crowell and we needed office space on Music Row). Steve Scruggs, Randy’s younger brother, started coming by my place in the evenings, a few times a week, with his guitar. He usually showed up around nine o’clock, fidgety and distracted, talkative and achingly lonely. He played me songs he was working on, and I played him some of my own. By this time I had become serious about songwriting myself, and wanted desperately to break through to a level of craft that I worshipped in the songs of Guy Clark, Mickey Newbury, Townes Van Zandt, and Rodney Crowell. I had not yet written a good song. Steve was a sweet friend, and if he had romantic motives when he visited me, he never let on, and we became very comfortable passing the guitar back and forth on those quiet nights.

Twenty-five years after moving to London, in October of 2001, I sat at my father’s bedside in the intensive care unit of a hospital in Nashville. He had just narrowly escaped death for the fifth or sixth time over the preceding several years. His precarious health was a constant and exhausting drama of acute and sudden illnesses followed by near-miraculous recoveries, and this latest medical catastrophe had left him jittery and depleted. I sat quietly holding his hand while he ran through his repertoire of tics—jerking, trembling, murmuring. Trying to think of something to engage his attention, I finally said, “I’m writing a book, Dad.”

He harrumphed, emphatically—one of the peculiar ways he liked to communicate.

I described one of the chapters to him: I am sitting on a beach, in Jamaica, staring at the sky and letting the tidal pull of my own future wash over me and draw me forward. I am full of my unlived life, and the joy of anticipation for it is taking me apart, cell by cell, and putting me back together in ways that could accommodate a thousand potentials. I am certain to outgrow myself. I can feel it all coming for me, and I am running to meet it in my deepest heart, in London.

&

nbsp; I was deliberately eloquent for him, describing my feelings in detail, the anticipation and the smell of the sea in the darkness, the brightness of the stars, my young, smooth feet in the sand, and the two silent boys at my side, like gargoyles protecting my dream.

He grew still and stared straight ahead through the glass doors to the nurse’s station while I talked. When I finished, he turned to me with surprise.

“You got me. With that chapter.” He thought for a moment. “I didn’t know you felt all those things then.”

Neither of us spoke for a moment or two; then softly I said, “Well, I did.”

Dad’s eyes glazed a bit, and he said quietly, “Just to think of you makes my heart swell with pride.”

Randy Scruggs married in April of 1976. He and Sandy are still married and have one daughter, Lindsey. He is a successful record producer, musician, and songwriter and owns his own production company and studio in Nashville. We renewed our friendship in our late twenties and have worked together many times. When I recorded my dad’s old song “Tennessee Flat-Top Box” in 1987, it became a number one hit, with Randy playing the signature guitar line.

I saw our dear friend John Rollins for the last time on New Year’s Eve 2000, at Cinnamon Hill, when I was there to see in the new millennium with my husband, John, and our baby, Jake. As John Rollins walked out of the house into the balmy evening, wearing his pink golf shirt and white trousers and wishing everyone a happy new year, I said good-bye to him and thought to myself very clearly, This is the last time I will ever see him. He died of a heart attack while taking his afternoon nap that spring, in his offices in Wilmington, Delaware.

Ted Rollins became estranged from his father for many years, and reconciled with him a few years before John died. Ted is still very close to our family and was particularly close to my father. He always made Dad laugh. When Dad was confined to a wheelchair in the last year of his life, Ted came over with silver paint pens and drew rocket ships and explosions all over the chair. He has become like a brother to me.

Brenda Cooper became a successful and respected Emmy Award-winning fashion stylist for television and film. We reconnected when she divorced and moved back to New York. The first time I appeared on David Letterman’s show, she accompanied me to allay my nervousness. Before the taping, we were in my dressing room with the door open when Letterman himself walked by. Brenda leaped from her chair and accosted him, shrieking, “You had better be nice to her!” Letterman was so taken with her animation, upper-crust accent, and striking looks that toward the end of my televised segment he called her out onstage. She took a seat next to me, and when he asked her if he had passed muster, she giggled and told him that he had indeed.

Sandy moved to New York, where I lost track of her. I think of her still.

Steve Scruggs committed suicide on September 13, 1992.

While writing this account, I received an e-mail from David, the son of the head of the British fan club for my dad who had so kindly appeared at the airport when I had first arrived in England and whose invitations to dinner I had never accepted. David had found me on the Internet and wrote to me, thinking that I would want to know that his father had just died.

Maurice Oberstein went on to have an illustrious career and was always respected as a gentleman in an ungentlemanly business. After his tenure as managing director at Columbia Records UK, he moved on to become CEO of Polygram International. He is credited with being one of the chief architects of the modern British recording industry. He died of leukemia in London on August 12, 2001, at the age of seventy-two.

In January 2007, I was in Sydney, Australia, playing at the State Theatre. When I arrived in my dressing room, I found a note from Derek Witt: “Remember me? We worked together.” I had not heard from him since 1977, so I called him when I was in London the following month. He had long since left the music business, and we had a nice long chat. He later sent me his photograph with an accompanying note that said, “I’m very happy with my lot in life.” Later that year, in November, the night before I was scheduled for brain surgery, I got a message on my cell phone that Derek had died.

Malcolm Eade is currently the vice president of international A&R for Epic Records UK. He is happily married with three children and is a grandfather. In our first phone call after twenty-six years, which left me in tears, he said to me, “I remember everything about you.”

Anthea Joseph died on Christmas Eve 1997 at the age of fifty-seven. She had been living alone with her two cats in the countryside outside London. She had ended her professional life in the music business as personal assistant to Obie at Polygram.

In 2009, my youngest daughter, Carrie, went to London for a short visit. She called me from Hampstead to ask me the exact address where I had lived, and then an hour later she e-mailed me a photo of herself, twenty years old, as I had been, standing in front of No. 3 Carlingford Road. A chill went through me; it was like looking at a photo of a time traveler who arrived where her mother had begun, with all the beauty, circumspection, and grace that I had longed for, and strained to glimpse.

Today, I can’t sit on a beach and look at the moon without realizing that my life is more than half over, and that the same moon that reproaches me now with my unlived dreams once drew me across the ocean with mysterious promises. My life was changed utterly by my six months in London. I often think that perhaps I didn’t stay long enough, but I’ve forgiven Dad for making me come home. It makes my heart swell just to think of it.

The word “contrition” comes from the Latin word for “bruise” or “grind,” a derivation that makes perfect sense to me as a former Catholic. Something in the drone and the rhythm of the Act of Contrition—“Through my fault, through my most grievous fault . . . ,” which I said to a man behind a screen in a dark confessional booth for so many years—was uniquely compelling. It took me many years to realize it wasn’t my fault, or even my grievous fault, however much I was drawn in by the swing of the words and the safe intimacy of confession. What all those anxiously droned Acts of Contrition chiefly accomplished was to break me down, bruising my sense of self permanently. Or so I thought. In any case, they had the immediate effect of making me withdraw from the truth about myself for a very long time. The truth about me, as it turned out, was unacceptable not only to Catholicism but to adults in general. The truth about me was not meant to fit into the system of convent school, religion, contrition, or punition. None of that mattered. I was a writer. It would save me.

One day in 1990, after I had finished my album Interiors and was beginning to write the songs for The Wheel, I went to my file cabinet and aimlessly pulled out a folder of papers my mother had recently sent me of my artwork, homework, and spelling lists from the seventh grade. Leafing through them I came upon an English project I had done on metaphors and similes. Reading the piece, I vividly remembered the excitement I had felt on being given this particular assignment, for it was the very first time in my entire career as a student that I had been excited about anything the nuns had ever asked me to do. I read through my discussion of metaphors and similes, and I could feel the thrill of my twelve-year-old self coming off the page, a nascent writer in love with language as if language were a potential lover. I came to a single page that said, in big letters I had printed very, very carefully, “A lonely road is a bodyguard.” It was a metaphor I had invented, and I was pleased with myself for having chosen this powerful image over the more straightforward simile, “A lonely road is like a bodyguard.” I lifted that sentence from my seventh-grade project and put it directly into a song I was writing, “Sleeping in Paris”:I’ll send the angels to watch over you tonight

And you send them right back to me.

A lonely road is a bodyguard

If you really want it to be.

That song ended up on The Wheel, and whenever I hear it now, or think of it, or sing it, I nod to my little girl self, and she, in the wisdom of her great distance and perspective, looks on with pleasure and the pat

ience of one who has waited a long time to be noticed. This one line, in this one song, is how I know who I am, and how I know I survived.

When I became a student at Vanderbilt in 1976, I declared a double major in English and drama, but I quickly discovered I could not break into the clique of drama students who got cast in plays because I was quiet, extremely shy, and a bit overweight. I also lacked any of the vibrancy or ambition that would have caught the attention of the teacher, whom I found somewhat distant and pontificating anyway. Two other professors, however, did make a great impact on me: Dr. Reba Wilcoxon, a tough and insightful English teacher who gave me the assignment to write a Menippean satire, which was one of the most memorable and exciting writing experiments of my life, and the great Walter Sullivan, eminent professor, authority on Southern literature (particularly the fugitive and agrarian movements), and a wonderfully lyrical author and teacher. When I arrived at Vanderbilt, he had been teaching there for twenty-seven years and went on to teach for twenty-three more, retiring in 2000. In his youth he had been part of a young writers group that included Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, and Robert Penn Warren. He was deeply inspiring in his gentle incisiveness, taking my terrible, saccharine, and sophomoric stories seriously, and encouraging me again and again to write “what I know.”

I loved his class, and he made me feel not only important but that I might actually have a future in writing. It was a promise that had been waiting for fulfillment—waiting since I was nine years old and won a poetry contest at school, waiting since I’d had the imaginative daring to conceive of a road as a bodyguard. But despite Professor Sullivan’s mentoring, Vanderbilt just didn’t work. I wasn’t a college girl. I was odd, removed, quiet, intensely lonely, and prone to living inside my own thoughts, often to my detriment and deep emotional disturbance. I didn’t care about the school at all, and lacking any of the natural enthusiasm of young women my age, I had no desire to socialize with my classmates. I wanted to be a writer, but becoming a good writer seemed an insurmountable and confusing task.

Composed

Composed