- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

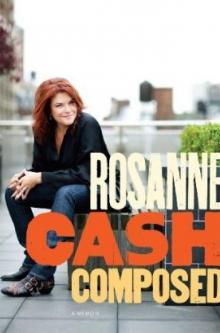

Composed Page 6

Composed Read online

Page 6

After finishing the academic year, I decided to move back to Los Angeles, where I enrolled in the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute. I was impatient with myself as a writer. I couldn’t see that I was getting better, so I thought I would try acting. I got an apartment on Fuller Avenue in Hollywood, close to the Institute, which was on Hollywood Boulevard at Highland Avenue. My father continued to subsidize me, paying my rent—$345 a month, an exorbitant amount in 1977—tuition, and living expenses.

I took to Method acting classes like a duck to water. I spent all day and evening, every day, at the Institute, I read Stanislavski as if it were the Bible, I watched the single existing film of Eleanora Duse, who was revered by Method actors, as if it held the key to all mysteries, and for six months I lived and breathed “The Work” with absolute and fierce focus. I was a Method elitist, and everything outside of the Institute appeared meaningless and colorless to me. I audited the classes that Strasberg—whom we were all encouraged to casually address as Lee—taught, but he scared me (and everyone else in the program) to death. He was brutal in his feedback, which he often used manipulatively. He might effusively praise an actor after a scene one week and completely ignore her the next, or spend an hour humiliating someone and then only casually remark “Nice work” to the other actor in the same scene. No one could predict his moods or understand his motives.

My own acting teacher, Dominic DeFazio, was an intense Italian who was also ruthless in his assessments of his students, but while he was tough he was also encouraging. I quickly developed an enormous crush on him, which I could barely conceal, leaving me flustered and frozen around him. But I wanted to learn, and the exercises he taught us for accessing buried emotion and for connecting the feelings to external content were enormously helpful to me in my personal life, and became even more useful later on, when I became a performer.

One scene I did for Dominic required me to cry on cue, and after weeks of rehearsal I was still consumed with anxiety about my ability to accomplish it. On the day of the scene I stood in the wings before going onstage in the classroom, absolutely petrified and certain that I would be unable even to walk out onto the stage. But I did go on, and when I got to the point in the scene where I was supposed to cry, I was delighted to find that my training had worked, and I produced the requisite tears. I then discovered, however, that I couldn’t stop, and I cried through the rest of the twenty-minute scene. At the end of it I took my chair in the center of the stage next to the other actor to wait for Dominic’s feedback. He paused and then said dryly, “Rosanne, your fee for films just went up to a million dollars.” I couldn’t have been more pleased with myself; after growing up as the girl who never cried, I was now the girl who couldn’t stop crying, albeit once removed from reality.

Within a few weeks I had made a number of friends at the Institute, something that didn’t happen in an entire year at Vanderbilt. Nadejda Klein, who was married to my dad’s agent, Marty Klein, at Agency for the Performing Arts, was a dark, sophisticated beauty with two children and a fantastic Eastern European accent. I copied her in almost everything—the way she dressed, her affectations, and her extralong More cigarettes, even though cigarettes held no appeal for me at all. I spent a lot of time with Nadejda, eating exotic lunches and, of course, fervently discussing The Work and our mutual obsession with the Duse film.

The first day of my cold-reading class, I took a seat on a bench outside the room where the session was shortly to begin. Next to me was a tall, beautiful girl about my age I had never seen before. We were both anxious, as the teacher was known to be tough, and cold reading allowed not only no preparation but myriad opportunities for humiliation. Suddenly, in the tense silence between us on the bench, the girl burst into tears. I reached out and took her hand, and we became friends from that moment on. She introduced herself as Kelly McGillis.

Another of my fellow students got a job in the television series Columbo, and it so happened that the episode for which he was hired, “Swan Song,” starred my dad as a traveling evangelist who kills his wife, played by Ida Lupino. After filming his scene, my friend told me that he had played a mechanic who was meant to be nervous and awestruck upon meeting my dad’s character. When I asked him what motivation he used to create the nervous excitement—the classic acting school question—he sheepishly replied, “I just used meeting Johnny Cash.”

It was, all things considered, a strange time in my life. A serial killer, the Hillside Strangler, was then on the loose in Los Angeles. My mother, seventy miles north in Ventura, was beside herself with continuous worry over me, with good cause. I sometimes left the Institute at eleven p.m. and walked obliviously into the dark, empty parking lot alone. Men followed me home from the supermarket. My apartment was broken into twice; the second time, all my jewelry was stolen, which devastated me. I told my father, who sent me a new piece of jewelry every week for several weeks. A pair of pearl earrings would be accompanied by a note saying, “My love is more precious than pearl earrings.” He got as far as “My love is more precious than Cartier watches” before he finally stopped. I still wear the Cartier Tank watch he gave me in that marathon of generosity.

I had affairs with a couple of fellow actors, neither of whom I felt particularly drawn to, but I thought it was something I was supposed to do. I was so desperately trying to find my real life, but I was frustrated and out of focus. I loved the class work at the Institute, but I had not gone out on a single audition, which most of the other students in the school were doing regularly. I started asking myself hard questions about being an actor: Was I just in love with the insulation the Institute afforded and the privileged, almost cultlike experience of being under the auspices of Lee Strasberg? Was my skin really thick enough for me to go out on auditions and get rejected over and over again? I knew in my heart that being part of a group of people who were singularly committed to an artistic ideal mesmerized me, but I recognized that I could not make a life as an actor. I could not bring myself to go on auditions, and the idea of drawing so much attention to my physical appearance, a significant part of getting a job, was absolutely horrifying. I was already obsessed with the worry that I had the wrong kind of nose to be a great actress. After comparing my small ski-slope nose with that of every actress I could think of, I found that not a single one shared my exact shape, which I interpreted as a fundamental indication of my lack of acting ability.

By December of 1977, I was floundering. The spell of The Work was wearing off, and I was a little panicked about my next move. I decided to get as far away from Los Angeles as I could, and I arranged to visit my dad’s friend Renate Damm in Germany for several weeks over the holiday break.

I arrived in cold Munich in early December and moved into the tiny spare bedroom of Renate’s apartment in the Siegfriedstrasse, near the English Gardens. I only knew Renate from touring in Europe with Dad and June, as she was the international liaison for their record label and always traveled with them. Dad had made the call to Renate to ask if she would host me for a short while, and she was incredibly gracious and welcoming. A decade older than me, she treated me like a beloved little sister. Her birthday was December 12, which was just a day or two after I appeared, and that night we went to a huge party for her at Ariola Records, the label where she worked. There I met many of her colleagues, and Renate told them all that I was an excellent songwriter. At this point I had written a dozen or so songs, most of them perfectly awful. One of the heads of the A&R department said to me, very seriously, that if I was to make a demo of them and send them to him, he would consider signing me to Ariola, to make a record to be released only in Europe. I was noncommittal, but I became secretly excited by the idea and later discussed it with Renate at length. After my truncated stay in London, I had been longing to move back to Europe, and quietly making a record in Germany and not having anyone in the States notice it would enable me to avoid any comparisons to my dad. I went back to Los Angeles and, with some trepidation, terminated my enrollment at t

he Lee Strasberg Institute. That was the end of my formal education.

Someone once told me to perform to the six percent of the audience who are poets. I have this in my mind at some point every time I sing, but I often have to find that six percent by looking past those who are yawning, glazed over, distracted, unsettled; those who come to try to look through me to see my dad; and those who can’t respond to music but like the experience of sitting in a crowd with those who can.

Sometimes, onstage, I am also one of those people who are yawning, glazed over, distracted, and unsettled. At some concerts I have felt as transparent as a pane of glass and haven’t been able to hear the music I’m making. Sometimes music has been so painful to me that I want nothing more than silence and the sound of waves. Sometimes the need to please the audience rises in me like bile and ruins everything.

T-Bone Burnett, an old friend, once told Joe Henry, “Don’t stop working, just stop worrying,” advice that Joe passed on to me that has since become my mantra. Now, even when I do worry, I keep working. Work, I remind myself, is redemption.

When the time came to produce four demos to send to Ariola, I called Rodney Crowell. I had met him only once, at a party at Waylon Jennings’s house in 1976, when I was still attending Vanderbilt. He was at the party with Emmylou Harris, her husband and producer, Brian Ahern, and his old friend and recording engineer Donivan Cowart. That night, when everyone started passing the guitar around, Rodney and Donivan played a song they had just written called “Leaving Louisiana in the Broad Daylight.” I was stunned. I thought it was just about the best song I had ever heard, and perversely my heart sank. Writing a song that good seemed so far out of my reach that I felt like giving up my dream of songwriting. I was rattled, and even a bit despairing. Susanna and Guy Clark, longtime friends of Rodney’s, were also at the party, and at some point in the evening Susanna introduced me to Rodney. He didn’t really seem to notice me, but I was riveted by him. Rodney had also written what I considered a definitive, world-class ballad, “’Til I Gain Control Again,” and he played rhythm guitar in Emmylou’s band. I had gone to see Emmylou at the Hammersmith Odeon when I lived in London and had taken note of the cute, lanky rhythm guitarist, never imagining that six months later I would be sitting in Waylon Jennings’s living room hearing him sing a new composition, and falling hard for him in the process.

I thought his particular sensibility would be perfect for what I wanted to do with my demos. I also thought it would be a way to get to know him and try to get him to like me. I don’t think I even understood what it meant to be a producer—I just knew he was a great songwriter and that if he could write those songs, we probably shared a similar musical aesthetic, or at least an aesthetic I could aspire to, and he could produce four songs for me. Years later, he always gave me credit for making him a record producer. When I called him, he said apologetically that he had never produced anything before. I told him that experience didn’t matter and that I knew he could do it, so we made plans to meet in Nashville, where he was living with his wife, Martha, and baby, Hannah. I was even more attracted to him after that first preproduction meeting. I remember telling June of my inner struggle over my growing fixation on him after we had met a number of times to work. When I asked her advice, she merely sighed and said, “Honey, if he’s married, it will never work. Just forget about it.” Odd advice, perhaps, given what had happened between her and my dad, but I tried to take it and to forget about Rodney. After the demos were finished, I sent them to Ariola, and they were pleased enough with the results that they offered me a recording contract, for the European market only.

Just before I left Los Angeles for Munich to begin the Ariola record, Renate came to see me. After we met with the lawyers who wrote up my contract, we made some social calls. Renate had made a point of introducing me to a wide variety of music when I lived with her in Munich. I’d seen Billy Joel at the beginning of his career, alone at a piano in a bar with only a few hundred people in the audience. I’d seen Bette Midler when she was first playing her character Delores DeLago, the mermaid in a wheelchair. (Some of the subtle, twisted humor was lost on the Germans, and I remember laughing louder than anyone in the audience.) But mostly we’d gone to hear jazz, as Renate was obsessed with it. I didn’t really get jazz, and it would be another decade before I came to appreciate it, but in retrospect that first introduction I got to jazz in Germany was very important, for I filed it somewhere in my mind until I had more life and musical experience to apply to the experience of listening to it.

Renate had a number of friends in Los Angeles who were in the jazz world, among them Herbie and Gigi Hancock and Jon and Maria Lucien. We went to Herbie and Gigi’s house one evening for dinner, and I was very quiet throughout—I felt at a loss to say anything intelligent or interesting to Herbie Hancock, who intimidated me completely. Renate started telling Herbie about my songs and how I was just about to make my first record. Then she asked if he would like to hear my demos, as she happened to have the tape in her purse. I was absolutely mortified and, flushing, protested, but Renate insisted. Herbie graciously accepted the invitation and after dinner settled back on his sofa while Renate put on the tape. He listened thoughtfully and nodded at me. “There’s something about your voice,” he said. Then he added, “Country music. I could get into that.” I let out a breath of relief, thinking, At least he didn’t seem to hate it. I begged Renate not to play it for Jon Lucien, and fortunately he was not there on our visit to his home, so we had a brief visit with Maria only. While I had no confidence in my vocal abilities at that time and very little in my songwriting, Renate’s lavish praise and encouragement, as well as her talking me up to everyone she came across, helped me develop at least a bit of assurance.

I wanted Rodney to produce the album, but Ariola was adamant that I record in Munich with a staff producer, Bernie Vonficht. So I returned to Munich and moved back in with Renate, and plans began for recording.

A few days before we were scheduled to go into the studio, I found myself unable to get out of bed. I couldn’t seem to get enough sleep, and when I was awake, I couldn’t think clearly. After a couple of days of this, Renate became alarmed and insisted on taking me to a doctor. “What’s wrong with her?” Renate asked, once he had posed a few questions and examined me. “She’s depressed,” the doctor said abruptly, and that was the end of the consultation. As he ushered us out, I began to accept the fact that I wasn’t entirely sure I even wanted to make a record. I had, I knew, been carefully avoiding reconciling myself to undertaking a project that, if successful, could help to make me famous. I wanted success, certainly, but I wanted it without the merciless exposure of a public life. I believed that I could be deeply satisfied and achieve success by becoming a great songwriter, but without being a performer. The idea of performing, of going on endless tours and living the draining, peripatetic life my dad was leading, was not appealing. From a very young age I’d spent enough time behind the curtain to not have any illusions about a performer’s life being one of glamour and excitement. The bone-crushing exhaustion, the constant vulnerability to media misinterpretation or even slander, and the complete obliteration of any semblance of a private life were not things I wanted for myself. My native reticence was not attracted to any part of it. But I did want the songs. I wanted to write them and I even wanted to sing them. I wanted to collaborate with other musicians, and construct arrangements and sonic textures and poetry, and get inside a rhythm and a beat, and go into the studio like a painter and create something from nothing. In the end, I wanted to do that so badly that I concluded that the benefits outweighed the attending risks, so I got out of bed and began sessions for my first record in the spring of 1978.

I went into the studio with Bernie and a band he had assembled, and though the first few days went relatively well, Bernie and I soon began to have some differences of opinion. Even though I was young and inexperienced, I had intuitive but very definite ideas about how I wanted to sound and what son

gs were right for me. My deep respect for great songwriters and my intense feelings about particular songs, songs I knew were pristine examples of true songwriting, were a guiding force in the studio when I found myself over my head and inarticulate about arrangements or sonics. This intuition became sharply focused when, midway through the initial tracking sessions, Bernie brought in a piece he wanted me to record called “Lucky.” I hated the song and said, as diplomatically as I could, that it was not right for me and that I didn’t want to do it. Bernie was equally adamant and we got into a heated argument, but I held my ground. The next day I showed up at the studio at the regular time to discover that he had called the musicians in an hour earlier to record the instrumental track, hoping that, on hearing it, I would capitulate and add my vocals. I refused again. He began shouting that the song would be a hit, and that if I wouldn’t record it, he would sing it himself. I told him to be my guest.

(Several months later, when the record was finished and released and I had gone back to Europe to promote it, I shared the pressrooms and television shows with another new artist and former record producer, Bernie Vonficht, who had had an enormous hit with a song called “Lucky,” as he had foreseen. Bernie looked at me warily in the pressrooms, as if embarrassed by his success, but I was genuinely glad for him. I wouldn’t have recorded the song even if I had known it would sell triple platinum. I knew I’d have to sing it for the rest of my life, and it wasn’t worth it.)

Composed

Composed