- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

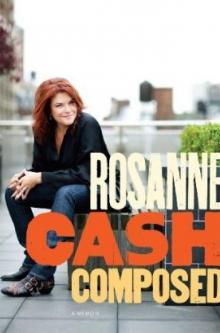

Composed Page 4

Composed Read online

Page 4

I was about to go through immigration at the Montego Bay airport the following day when I realized that I had left my coat at Cinnamon Hill. I was going to step off the plane in London into a winter day, and I was wearing only a girlish, almost infantile sundress of pale blue, with short puff sleeves and a modest square neck, that came just to my knees. Ted Rollins, ever present and so eager to please, immediately volunteered to have Dad’s security guard drive him at top speed to Cinnamon Hill to retrieve the coat. He brought it to me minutes before my flight took off, and I hurled thank-yous at him as I sprinted happily out onto the tarmac. I took my seat in first class—Dad treated me very well in those years I spent with him after high school—next to a distinguished-looking English gentleman. After quizzically looking me up and down, he leaned over and said with a smile, “Pardon me, but could you sign this paper for my daughter? I’m sure you are a very famous rock star, and I don’t know who you are, but she will know.”

Embarrassed, I said, “No, sir, I’m not. She wouldn’t know who I am.”

He shoved the paper at me. “Please,” he said, and smiled again. I signed the paper, flushed, guilty, and excited. My new life was in full swing, and the plane hadn’t even taken off.

I arrived in London with the sheen of anticipatory greatness worn a bit dull due to exhaustion and creeping uncertainty. From the view in Jamaica, London was nothing less than Oz. Emerging from customs, it was just a big, crowded airport. Hundreds of people, looking for other travelers, fixed their eyes on me momentarily as I came through the automatic doors into the terminal. I was alarmed and started to turn around. A throng of tired new arrivals were at my heels, and I swung back around and pushed my cart forward, red faced and grim.

In 1976 I was, despite my grand plans and bravado, a timid girl. I had asked a member of the sound crew from my father’s last European tour with whom I had become friendly to meet me at the airport and drop me at my hotel. I passed the crowd and the length of the barricade without seeing him. I waited near the front doors to the terminal until he showed up, nearly half an hour later. He seemed distracted and not terribly happy to see me and quickly ushered me into his car, where we rode in silence to my hotel. When I mentioned getting together later, he mumbled that he had plans. It was the only time I saw him during the six months I lived in England.

I had sent my trunk ahead of me, which had been retrieved by the copresidents of my father’s fan club in Britain, a kind and devoted couple who were very gracious and solicitous of my welfare as a young girl on my own in a foreign country. They had shown up at the airport unannounced just as my other ride arrived, but I was eager to go off with the young man, who held the promise of excitement and fun and new friends, and I politely declined their offer of a ride. They invited me to their house for dinner several times over the next few months, but I had decided that they were probably dull and conservative and imagined strained conversations about my father over glasses of sherry. I always found an excuse not to go. To this day I feel twinges of guilt about my lack of appreciation and courtesy.

I stayed at the Portman Hotel for three weeks while I looked for an apartment. Dreary Portman Square was full of sullen businessmen passing through in gray suits, but it was the only hotel I knew, as I had stayed there on my last trip to London, and I did not have imagination enough to search out a better place.

My dad had arranged a job for me at his label, CBS Records. I had begun a major in music theory at the community college I’d attended, but I had no real understanding of how the music business worked and no office skills whatsoever.

Maurice Oberstein, the president of the UK division of the label, met with me in his office and asked about my interests and abilities, graciously treating me as if I were a valuable new asset to the company rather than a favor to be done for the child of one of his top artists.

I was nervous and subdued, but I gamely tried to present myself as a young woman who would bring a fresh perspective to the company. At the end of the conversation, Obie told me that he would pay me forty pounds a week, under the table, and assigned me to the position of assistant in the artist relations department under the supervision of Derek Witt, über-publicist and the first outright queen I ever knew. Derek’s codirector in the artist relations department was Anthea Joseph, legendary cofounder of the Troubadour in London. When Bob Dylan arrived in London in 1963, he brought a note with him from Pete Seeger: “Find the Troubadour. Ask for Anthea.” She was the first person to put him on a London stage, and she is immortalized in one scene of the epic 1967 Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back, in which she is being reassured by Bob after a hotel glass-breaking incident. Her main job at CBS seemed to be smoking heavily and having lengthy and intense phone conversations and lunches with musicians, artists, Communists, and intellectuals of all sorts.

Anthea had a tremendous influence on me. Her intellectual rigor, combined with an eccentric personality and a passion for music, was absolutely riveting—as was her own oddness. Tall and angular, with a great gap between her two front teeth, stringy brown hair, and social service wire-rimmed glasses, she wore narrow jeans and low-heeled boots as a virtual uniform, which in 1976 I read as sartorial code for an anarchist. It was thrilling. Her perpetual expression was one of bemusement at some private joke combined with an intense, piercing gaze. At the same time she had a permanent air of exasperation because she knew no one could ever meet her intensity head-on. She was the subject of an inordinate amount of gossip and resentment from people in the department who complained that she didn’t actually do any work, but I thought we were incredibly lucky that she deigned to show up at all. I longed to know what Anthea knew. I wanted to listen in on her conversations, and I wanted her experience and her biting tongue. My own intellectual rigor was nonexistent and my sophistication was nascent at best, but Anthea was extraordinarily tolerant of me, even congenial, and I knew her feelings were genuine, because she never hesitated to take me to task when she felt it was warranted.

I developed a friendship, and a terrible crush, on Malcolm Eade, a young man whose office was at the opposite end of the floor from mine on the way to the coffee room. I managed to make myself available to fetch coffee for everyone in the department, several times a day, so that I could stop by Malcolm’s office for a chat, or just peer in at him soulfully as I went by. He was fair-haired and boyish, well mannered and shy, which at the time seemed to me to be a great deal to recommend any man my age. I spent so much time in his office that it’s hard to believe I didn’t get him fired. I myself could not be fired, as I did not have a real job, but Malcolm, in his kindness, allowed me to test the parameters of my newly formed and awkward notions of enticement as I sat in the chair opposite his desk. Nothing ever happened between us, not even a kiss, but I had never felt so perfectly accepted by any man. I tried out all sorts of personalities and opinions in front of Malcolm, and if I tested his patience, he never once let on. If Anthea was a slightly terrifying but endlessly compelling role model, Malcolm was a seductive and innocent dream.

I was given a desk that was crammed into the corner of the office of a department staff member, David, and it somehow never managed to cross my mind that he might well have considered me an intruder: Johnny Cash’s kid on a lark in London, taking up a good deal of his space for the purpose of absolutely nothing that he could ascertain. Still, he was kind, and did not even resent his orders from Derek to take me around to find a flat. David did suggest that we tell prospective landlords that I was his secretary, “to make things smoother.” I self-importantly balked at this, as he was not senior enough to have a secretary, and the plan felt strangely lascivious to me, but I see now that that little ego stroke was the very least I could give him in return. Eventually, he did help me locate a flat, a small, lovely third-floor walk-up at No. 3 Carlingford Road, in Hampstead. (Later, I met David’s fiancée, an immaculately put-together and aggressive blonde who favored shiny suits in shades of steel gray with matching stiletto-heeled boots, had perf

ectly straight and sleek almost-white hair, and wore near-Kabuki-style makeup. She scared me to death, though she dripped honey when she spoke. One evening shortly after my arrival, as we were having drinks after work at a wine bar, she thoroughly looked me over and said thoughtfully, and not unkindly, “You aren’t very glamorous, are you?” I didn’t answer, in part because I wasn’t sure if I should be insulted, and in part because I wasn’t sure what the answer was. After many years of wrestling with that question, I decided that she was partly correct. I like a little glamour, just not so obvious, and a bit more rock and roll than business dominatrix.

It soon became clear that my job in artist relations would involve little more than deciding which seats various people in the company would be given for concerts by CBS artists performing in London, and then doling out the tickets when they came to David’s and my office to retrieve them. At one point, when several artists were playing in London at the same time, David and I posted a sign on our door that read CBS BOX OFFICE. QUEUE HERE. (By the end of my London stay, a few Anglicisms had seeded themselves into my mind, forever to remain: the proper use and spelling of the word “queue,” the reversal of month and day when writing a date, and an obsessive and unrelenting adherence to teatime, with proper tea brewed in a pot.) When we strategized seat placements for concerts, we began with the given that Obie always got center orchestra, six to eight rows back from the stage, depending on the venue. After Obie and his wife, there was a strict hierarchy for bestowing seats, with the heads of each department at the top and with secretaries at the very bottom. This pecking order was taken with utmost seriousness, and it was an unspeakable breach of protocol to give a mediocre seat to a self-inflated A&R guy. When I inadvertently made such assignments in my early days at the job, I would get a personal visit from the offended party, which would leave me withered, shaking, and in tears. I felt sorry for the secretaries, who were mostly relegated to the balconies, and even sorrier for the occasional member of the cleaning staff who ventured to ask for a ticket to see a favorite artist, to whom I was ordered to give back-of-the-balcony seats. I sometimes managed to elude David’s observant eye to give one of these lower-echelon workers a center orchestra seat.

The CBS office building was in Soho Square, just off Oxford Street. I took the tube to work every morning from Hampstead and got off at the Tottenham Court Road station. My office was on the sixth floor, and I strove, with utmost diligence and gut-churning dread, to stay away from The Third Floor, which housed A&R and promotion. No woman was safe there; the taunts and come-ons were urgent, and not friendly. The men in those two departments were notorious: loud, predatory, debauched, and dependably drunk by four in the afternoon. They started drinking, as well as ingesting other substances, early in the afternoon, and most of the women I knew in the company absolutely refused to go to the third floor anytime after lunch. In the mornings, when they were still hungover, it was relatively safe if you got in and out quickly; if it was essential to go there in the afternoon, you took a friend. Whenever I had to deliver tickets or a memo there, I would step out of the elevator and stand frozen in terror for several minutes, sweating and trying to calm myself, nearly coming out of my skin in fear, before I could work up the courage to push open the double doors to their offices. Sometimes, going down in the elevator to the lobby, I could hear a muffled roar as we passed The Floor, and I would shudder in relief as I glided past in a silent, sealed box.

The staff of the art department was equally crazy but without the misogyny and maliciousness of the promotion guys, and I became friends with several of them. They teased me mercilessly about my American ignorance. I was told that corgis were the queen’s favorite breakfast cereal, that the town Slough was pronounced “sloff,” and that black pudding was made of cherries. I was the source of a tremendous amount of amusement for the lads who did up the album covers, and, actually, I was glad to oblige.

I loved Hampstead, and I loved the image of myself there, as a young and slightly starving albeit plump artist in formation, alone but comfortably taken care of in a nice flat in an expensive part of town, with the rent paid by my dad. I tried to live on the forty pounds a week, but it was not easy, given the proximity of the antique markets at the top of Hampstead High Street. I had developed a serious penchant for antiques at the age of eighteen, a love which has stayed with me throughout my life, and I spent most of my money on old teacups and plates and ivory-handled fish knives. Whenever I was at home in my flat, I began listening to four records on continuous rotation: Bob Dylan’s Desire, Tammy Wynette and David Houston’s album of duets, James Taylor’s Gorilla, and Janis Ian’s Society’s Child. These four records wore grooves in my personality, I listened to them so much. They held the entire content of my experience and my hopes. I had no interest in going to the Heath, the nearby park that everyone went on about as being so beautiful and peaceful. I did not care about peace and nature in the least; what I cared about was music, men, food, antiques, excitement, and being pretty.

I quickly became very close to a girl named Sandra Cooper, who was a couple of years younger than me and worked on the artist relations floor as a temp. Sandra had an identical twin sister, Brenda, who also occasionally worked on the same floor and who lived with one of the lighting directors for the band Yes. Although Sandy was initially suspicious of me and avoided me, I was attracted to her, mostly because she had a bracingly caustic attitude and a fierce, musical laugh. One day I passed her desk on the way to my crammed office and made a joke to her about having to go to the third floor, and she opened up immediately. She and Brenda were both very fashionable, very thin, perfectly made up, and always tottering on extremely high heels. I took their lead and bought a pair of six-inch wedged heels, which I wore constantly (except for days it snowed), and a brown velvet blazer. I also invested in a pair of Fiorucci jeans, very tight, to try to look more like them, but my size 32’s did not have quite the same effect as their size 28’s. Sandy and Brenda and I started going to lunch together every day, usually to a Greek restaurant near Soho Square that served grilled grapefruit as an appetizer followed by souvlaki or kebabs. As Sandy and I were constantly broke, Brenda, who was nicely taken care of by her music business boyfriend and who had her own income from different sources, mostly relating to fashion, paid for our meals. Brenda wore a red baseball cap every day of her life due to a chronic displeasure with her hair. One day, a couple of months into our friendship, she showed up at lunch panicked, because she had to attend a black-tie event and could not figure out how to make the baseball cap go with her evening gown. I never saw the top of her head during my entire stay in England. I loved the twins’ energy, their toughness, and their good-natured, and sometimes vicious, sniping at each other. They showed me how to thicken my own skin, how to dry up some of my cloying natural sentimentality and cultivate a more urbane sense of humor. I would never have had the courage to become the person I was turning into without both Anthea’s template for intellectual and musical depth and the wild influence of the Cooper twins.

I was, I began to notice, gaining weight. The year before I had had a tumor removed from my left ovary, and had begun to develop another before I left for England. My doctor at home had started me on an injectable hormone that I had to receive every three months, which tended to make me fat. Soon after my arrival I found a private doctor in Belgravia who consented to administer the injections. The first time I visited him, I was led into his inner office, superbly appointed with mahogany and leather, and was shown to a seat in front of his polished desk. He smiled in greeting and said, “Well, first thing, let’s see your figure.” I had to stand and remove my brown velvet blazer, and turned slowly around in front of him in a state of increasing mortification. My figure was by this point dumpy and broad in the hips, and I could see by his curt nod that he thought so as well. He gave me the shot every couple of months, for an extraordinary fee, and I just continued to grow heavier.

Early in my stay in London, the second day of my fr

iendship with Sandy, we went to the Hard Rock Cafe, which in 1976 was brand new and outrageously trendy. It was cold, so we walked quickly from the Portman, and every man who walked by us turned to stare frankly at Sandy. She suggested we join arms so that they would think we were lovers, and we linked together. The male stares now became embarrassed glances, and Sandy played the routine up, squeezing me and whispering in my ear. We entered the Hard Rock, and again all the male eyes in the place turned toward Sandy. As soon as we sat down, a young man came directly over to her and asked her to join him and his friends. She responded with a withering comment, which I can no longer recall, and he recoiled and walked away silently. The few seconds that passed between his invitation and her reply were torture for me. Not knowing the rules, I was terrified that she would leave me sitting alone at this very prominent table, swathed in brown velvet, with my lackluster hair-cut, swollen body, dearth of makeup, and Dubonnet on ice. I was inexpressibly grateful and loved her for her loyalty.

It was at the Hard Rock, on a subsequent visit with Sandy, maybe a week or two later, that I heard Bruce Springsteen for the first time. Everyone had been talking about him. I had read about him in Melody Maker, like everyone else in the music business in London, but I had not yet heard his music. I was sitting at the bar at the Hard Rock, Dubonnet in hand, when “Born to Run” came on the sound system. Sandy was talking to me, but I could not hear a word she was saying, so riveted was I to the music. The combination of urgency, poetry, testosterone-fueled guitars, and the relentless backbeat made me literally weak in the knees. It was as if William Blake had put on black leather and climbed a motorcycle. I was enraptured. I couldn’t begin to conceive that, thirty-three years later, I would do a duet with Bruce Springsteen on my album The List. That concept belonged to someone else’s life in 1976, not the shy, round girl sitting at the bar of the Hard Rock Cafe in London.

Composed

Composed