- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

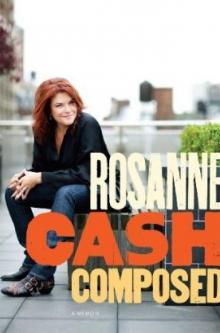

Composed Page 14

Composed Read online

Page 14

That was June. In her eyes, there were two kinds of people in the world: those she knew and loved, and those she didn’t know and loved. She looked for the best in everyone; it was a way of life for her. If you pointed out that a particular person was perhaps not totally deserving of her love, and might in fact be somewhat of a lout, she would say, “Well, honey, we just have to lift him up.” She was forever lifting people up. It took me a long time to understand that what she did when she lifted you up was to mirror the very best parts of you back to yourself. She was like a spiritual detective: She saw into all your dark corners and deep recesses, saw your potential and your possible future, and the gifts you didn’t even know you possessed, and she “lifted them up” for you to see. She did it for all of us, daily, continuously. But her great mission and passion were lifting up my dad. If being a wife were a corporation, June would have been the CEO. It was her most treasured role. She began every day by saying, “What can I do for you, John?” Her love filled up every room he was in, lightened every path he walked, and her devotion created a sacred, exhilarating place for them to live out their married life. My daddy has lost his dearest companion, his musical counterpart, his soul mate and best friend.

The relationship between stepmother and children is by definition complicated, but June eliminated the confusion by banning the words “stepchild” and “stepmother” from her vocabulary, and from ours. When she married my father in 1968, she brought with her two daughters, Carlene and Rosie. My dad brought with him four daughters: Kathy, Cindy, Tara, and me. Together they had a son, John Carter. But she always said, “I have seven children.” She was unequivocal about it. I know, in the real time of the heart, that that is a difficult trick to pull off, but she was unwavering. She held it as an ideal, and it was a matter of great honor to her.

When I was a young girl at a difficult time, confused and depressed, with no idea of how my life could unfold, she held a picture for me of my adult self: a vision of joy and power and elegance that I could grow into. She did not give birth to me, but she helped me give birth to my future. Recently, a friend was talking to her about the historical significance of the Carter Family, and her remarkable place in the lexicon of American music. He asked her what she thought her legacy would be. She said softly, “Oh, I was just a mother.”

June gave us so many gifts, some directly, some by example. She was so kind, so charming, and so funny. She made up crazy words that somehow everyone understood. She carried songs in her body the way other people carry red blood cells—she had thousands of them at her immediate disposal; she could recall to the last detail every word and note, and she shared them spontaneously. She loved a particular shade of blue so much that she named it after herself: “June-blue.” She loved flowers and always had them around her. In fact, I don’t ever recall seeing her in a room without flowers: not a dressing room, a hotel room, certainly not her home. It seemed as if flowers sprouted wherever she walked. John Carter suggested that the last line of her obituary read: “In lieu of donations, send flowers.” We put it in. We thought she would get a kick out of that.

She treasured her friends and fawned over them. She made a great, silly girlfriend who would advise you about men and take you shopping and do comparison tastings of cheesecake. She made a lovely surrogate mother to all the sundry musicians who came to her with their craziness and heartaches. She called them her babies. She loved family and home fiercely. She inspired decades of unwavering loyalty in Peggy and her staff. She never sulked, was never rude, and went out of her way to make you feel at home. She had tremendous dignity and grace. I never heard her use coarse language, or even raise her voice. She treated the cashier at the supermarket with the same friendly respect that she treated the president of the United States.

I have many, many cherished images of her. I can see her cooing to her beloved hummingbirds on the terrace at Cinnamon Hill in Jamaica, and those hummingbirds would come, unbelievably, and hang suspended a few inches in front of her face to listen to her sing to them. I can see her lying flat on her back on the floor and laughing as she let her little grand-daughters brush her hair out all around her head. I can see her come into the room with her hands held out, a ring on every finger, and say to the girls, “Pick one!” I can see her dancing with her leg out sideways and her fist thrust forward, or cradling her autoharp, or working in her gardens.

But the memory I hold most dear is of her two summers ago on her birthday in Virginia. Dad had orchestrated a reunion and called it Grandchildren’s Week. The whole week was in honor of June. Every day the grandchildren read tributes to her, and we played songs for her and did crazy things to amuse her. One day, she sent all of us children and grandchildren out on canoes with her Virginia relations steering us down the Holston River. It was a gorgeous, magical day. Some of the more urban members of the family had never even been in a canoe. We drifted for a couple of hours, and as we rounded the last bend in the river to the place where we would dock, there was June, standing on the shore in the little clearing between the trees. She had gone ahead in a car to surprise us and welcome us at the end of the journey. She was wearing one of her big flowered hats and a long white skirt, and she was waving her scarf and calling, “Helloooo!” I have never seen her so happy.

So, today, from a bereft husband, seven grieving children, sixteen grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren, we wave to her from this shore, as she drifts out of our lives. What a legacy she leaves; what a mother she was. I know she has gone ahead of us to the farside bank. I have faith that when we all round the last bend in the river, she will be standing there on the shore in her big flowered hat and long white skirt, under a June-blue sky, waving her scarf to greet us.

For Dad’s funeral I chose a black knee-length Armani skirt and a Philippe Adec jacket with sweet black-on-black appliqué flowers on one shoulder. I wore black stockings and the same Prada satin pumps, which still had bits of dried mud on them from June’s funeral four months before.

I fainted at the funeral home. I came to on the floor with my aunt shaking some sense into me and my husband yelling at me to breathe. Tara waited until I was on my feet and fully conscious and then reprimanded me, and rightly so. “Get a grip. Your children are here,” she said.

The eulogy I delivered at his funeral, in the same vast church, was not nearly as articulate as the one I wrote for June, since over the course of the previous four months I had lost a good deal of the natural grace and power of my vocabulary:I have no words that can say who he is, or what we feel.

But on behalf of Kathy, Cindy, Tara, John Carter, and myself, we mourn with the very essence of mourning the loss of two connected but separate Beings: Johnny Cash and Daddy. The larger-than-life qualities of this luminous soul—his poetry, his voice, his compassion and humility, his pure love and equally pure pain—if those qualities were distilled down to a series of small, private, and precious moments, that is where we found our daddy. It was not the scope of his artistry and his remarkable body of work which made him great. He was already great. The music just came out of it. He was not famous when he taught us to water-ski, or fish, or how to make ice cream out of snow. He was not a performer when he walked us down the aisle or stood by us at our weddings, or sang his special song reserved for his newborn grandbabies (which went, “Boom-ba-ba-Boom, Boom-ba-ba-Boom . . .”). He was not an icon when he told us how he loved us, how beautiful and handsome we were, how proud he was. He never criticized, he never condescended to us, never forced his will on us, never raised his voice or lectured. He offered advice only when we asked for it, and then he would measure his words with respect and kindness. He respected us as much as we respected him. He was so modest and humble, and so willing to live with the weight of his own pain without making anyone else pay for it.

He was a Baptist with the soul of a mystic.

He was a poet who worked in the dirt.

He was an enlightened Being who was racked with the suffering of addiction and grief.

/>

He was real, whole, and more alive to the subtleties of this world and the worlds beyond than anyone I have known or even heard of.

He was the stuff of dreams, and the living cornerstone of our lives.

I can almost live with the idea of a world without Johnny Cash, because in truth there will never BE a world without him. His voice, his songs, the image of him with his guitar slung over his back, all that he said and sang and strummed changed us and moved us and is in our collective memory and is documented for future generations.

I cannot, however, even begin to imagine a world without Daddy.

The best thing I could wish for him now is that all his beliefs are coming true.

For my stepsister Rosey’s funeral, six weeks after my dad’s, I wore a short, black felt wool Club Monaco skirt, my twenty-year-old Yohji Yamamoto collarless jacket, black tights, and knee-high boots. I could not face the satin Prada pumps one more time. Her widower spoke to the congregation, in the modest funeral home parlor, about the vast quantities of drugs Rosey liked to ingest, and proceeded to tell the story, infamous in our family, of the Thanksgiving dinner when Rosey was asked by her mother what she would like as a gift for Christmas that year. She replied, staring at my brother without a trace of humor, “I guess I’d like a penis, because that’s the only way anybody gets any attention around here.” It was at that moment in the service that I decided that an extemporaneous eulogy was in order. Leaning over to my sister and brother to tell them I was going to speak, I quickly got up out of the pew. I don’t remember what I said then; I just wanted them to forget what he had said. I was utterly exhausted. I absolutely could not take anymore, I remember thinking, with some anger. This was not a taunt to some higher power to see how serious I was about having reached my limit, but it was perhaps taken that way, as things turned out.

In 1977, I was on a flight from Munich to Montego Bay. There were a few legs to the trip: Munich to Frankfurt, Frankfurt to New York, New York to Jamaica. My dad and June were already at Cinnamon Hill, where I planned on joining them for a few weeks of vacation. When the plane stopped in New York, an agent from the airline got on and came to my seat.

“Miss Cash? We have a message from your father in Jamaica. He says to tell you to get off the plane. There is a hurricane in the Caribbean, and he is concerned about your safety.”

I got off the plane. I had only about a dollar in my purse. Fortunately, I had a single credit card, which apparently worked, and which I used to check into a hotel near JFK, where I waited a couple of days for the hurricane to pass before getting back on a plane to Jamaica.

That little incident might well stand as representative of what happened to me constantly when I was coming of age, which I recall as a series of bizarre interruptions, rapid changes of plans, stops and starts, occasional great events, and temporary but intense confusion. I was always without money, but somehow I managed to travel the world first-class; find comfortable places to live and unusual, interesting people to stay with and go out with to restaurants and music clubs; sign contracts for grand ideas; work my way into peculiar circumstances in remote locations; and generally live off the grid, and outside the normal patterns of young adult development. This template of constant change and inverse experience stayed with me through my twenties and thirties. It resonates less now, though my life is no less chaotic and full of travel, but my internal discipline and sense of structure override its influence.

In the spring of 1978, I got off a flight from Munich and was kept in customs for three hours in Los Angeles because I had failed to declare some clothing I had bought in Germany. When I finally left the airport after paying a heavy fine and having my name entered into the computer with a red flag for the next seven years, making every international trip a miserable inconvenience, I went straight to my stepsister Rosey’s apartment, in a very unfashionable section of Los Angeles off La Brea Avenue. She was not at home, so I removed a window screen, forced her window open and slipped inside, took a shower, and went straight to a record release party for my stepsister Carlene at the Magic Castle in Hollywood. There I met Rodney Crowell, and that was the night that began our romance, after the unrequited love on my part, and the demos we made together that got me the Ariola contract. We remained together from that night for the next thirteen years.

Then, my mother. My youngest sister and I sat with her body, alone, for an hour after she died, both of us surprised that the nursing staff let us remain. I went with my stepdad, Dick, to pick out the casket and the headstone, wrote the inscription for the headstone, and submitted it for my sisters’ approval. I went to the funeral home with all of them and decided on the format of the services, I agreed to the autopsy, and I wrote another eulogy. By now both the Armani and the Jil Sander were out of the question, as none of my clothes fit properly. I was swollen with shock and fear. I wore pearls and an old black blazer and a black skirt that was coming apart at the seams, and I resurrected the damnable black satin Prada pumps. I got them out just a few days ago, and they are still encrusted with mud.

The last eulogy I wrote was for my mom, on May 24, 2005. I delivered it at Sacred Heart, her longtime parish in Ventura:My mother was a gardener. She loved flowers and plants and everything that bloomed, and everything that bloomed loved her back. All of nature seemed to blossom in her presence. She had no prejudice—she treated the industrial boxwood or hedges with the same care as the fragile orchid or the jasmine, or her prize roses. I always stood in awe of what my mother could do with things that grew in the earth. It seemed that just her presence had an energizing and nurturing effect. And so it was with us, her children. During our fragile moments, our struggles, and our dark nights of the soul, she treated us with the extra care she would a hothouse orchid. She was attentive, and kind, and gave just the right amount of nurturing—not too much to suffocate, or too little to starve. When we were wayward and rebellious, or ill-mannered and negligent, she was not afraid to prune us like an errant vine with the authority of her voice and command; she was the gardener and we would grow according to her design. The plant did not talk back to the gardener. And how grateful we are for that today, as grown women with children of our own.

When I woke this morning, my husband and I were talking about the difficult day ahead, and about my mother and her legacy to us. And John said, “Your mother was the definition of a life well spent. She was always engaged, in her children, her friends, her faith, and her whole community. It’s inspiring. That’s how we all should live.”

It’s so true. I can look at the beauty in my life, the sacred space of my home, and the faith in my heart, and witness the love, consideration, and good manners of my children, and I have to thank my mother. She taught me how to do that. She taught me how to find the beauty, how to teach the child, how to be fierce and loyal, how to love unconditionally, and how to be happy—which by itself is an extraordinary gift. There was no higher calling to her than making a home and being a wife and mother. She was as devoted and confident as a wife, first to my father for thirteen years and then to Dick for thirty-eight years, as she was as a mother. And then, as a grandmother, she was exalted. She filled in all the gaps, she ordered their universe on a foundation of love.

When I was a teenager, my home was always open to my friends, at any time of day or night. My mother never required advance notice or permission. She was always effusive in her welcome, interested in our lives, entertained by our teenage wackiness, and, if we went too far, as my friend Peggy and I did when we left school one day and took an impromptu trip to Mexico, she was imperial in her fury. I was grounded for months. Thank you for that, Mom.

My mother was the source of endless love and constant devotion, but she was also the immovable wall, the firm limit and the guiding light, until we were wise enough to provide those things for ourselves. Some of us took longer than others, even well into adulthood, but she never wavered in her example of strength and wisdom, and in her belief that we would show up clean, perfectly gr

oomed, well mannered, and a productive and vital member of society. I will spend my life with those expectations ever in front of me, and thank God, and Mom, for that.

My mother died on my fiftieth birthday. The day before, I saw it coming. I could see where she was headed, and I was devastated at the symbolism, which I could not even begin to understand. I could not imagine why her soul, and her plan with God, included linking her departure from this earth with the day I was born. I felt as if I were in a dark cave, groping at the walls for direction and meaning. Over the last few days, I have begun to get a glimmer of understanding, although it may take the rest of my life to fully decode the profound message she gave me. She loved birthdays. They were extraordinarily important to her—not just the birthdays of her husband and children, but her own birthday, and that of her extended family and friends, even acquaintances. She remembered the birthdays of people who were long passed, or people she hadn’t seen in years. She would remark that it was someone’s birthday, and oftentimes we wouldn’t even know who that person was. In fact, I know that she had birthday cards carefully signed and addressed to different people, for Dick to send out after she was admitted to the hospital. The day of a person’s birth was significant to her, even if the person was only marginal in her life.

Composed

Composed