- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

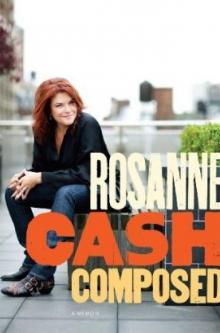

Composed Page 13

Composed Read online

Page 13

I went on performing in the shadow of these great role models, and more—Linda Ronstadt, Joni Mitchell, Grace Slick, Janis Joplin, Judy Collins, Laura Nyro—always questioning, always judging my own instrument, until one day in August of 1998, at a gallery opening I attended with John. I began to talk to someone in the crowd when I discovered I could not be heard because I was unable to get my voice above a rasp. As we walked out, John remarked, “Your voice has been like that for a few weeks. You should get it checked out.” I said it was probably allergies and forgot about it, as I was more concerned at the time about being four months’ pregnant and still suffering miserably from morning sickness. September passed, and my voice did not get better. I had a show scheduled for the following month—a big benefit for a hospital in California—and as the date approached, I grew more and more worried about my voice. I drank teas with honey, took various lozenges, sprayed it, gargled it, and doused it, but I sounded more and more like Tom Waits with a bad cold. The day of the show came and I was nearly mute. I went out onstage, praying that a miracle would happen and my voice would reappear just in time. After croaking my way through a few songs, I exasperatedly asked the crowd of hospital administrators, “Is there a doctor in the house?”

I made an appointment with Dr. Gwen Korovin, an ENT who takes care of singers. She put a camera down my throat, and when the image appeared on the screen, she stepped back as if someone had jumped in front of her. I had polyps, and they were huge, covering the entire left side of my vocal cords. Gwen stammered that she had not seen polyps this large on someone who had not been a heavy lifetime smoker, so she did not understand it. (She was certain, gratifyingly, that I did not have cancer.) While puzzled, she knew for certain that they had to be removed, and we scheduled surgery for six months after the birth of my baby, who was due in January.

As my pregnancy progressed, I grew even hoarser. Gwen checked my vocal cords shortly before I gave birth and shook her head. “The bigger you get, the bigger the polyps get,” she said.

I gave birth to my and John’s son, Jake, in January. I was overjoyed that at the age of forty-three I had given birth naturally to a healthy eight-pound baby boy, but I was bereft that I could not even sing him a lullaby. In March, Gwen attended a conference in Paris, where a husband-and-wife team (an obstetrician and an ENT) gave a talk on hormones and polyps. Gwen spoke to them about my case after their presentation. “Don’t operate,” they urged her. “The polyps will go away when her hormones return to normal, after breast-feeding.” During the fourteen months I nursed him, I had my doubts that I would ever have a voice again, but they were right: Six months after that, the polyps had disappeared. But my voice was a mess. Gwen sent me to William Riley, a vocal coach and voice therapist, to rebuild it. I was terrified when I started to sing for him that he would tell me it was useless, that my voice was irreparably damaged, but at the end of an hour he said, “You’re just seriously out of shape. You can get it back.” We spent the next year rebuilding my voice from scratch. During those long, frightening days of near-muteness, I vowed that if my voice ever returned, I would give up the internal monologue of self-criticism about it. I promised myself that I would enjoy it, for a change. And I did. I saw my voice in a whole new way once I really did get it back. It was so much stronger than I had believed, so much more lithe and nuanced. It was like meeting an old friend who I had not appreciated in my youth but who became a close and cherished companion in my middle age.

Jakob William Leventhal was born on January 22, 1999. I thought I knew just about everything there was to know about parenting after twenty-plus years of motherhood, but what I knew about was mothering girls. I had never believed that raising boys could be that different, but I soon discovered how wrong I was. I have grown to deeply love and respect the emotional singularity of the male psyche, particularly after decades of trying to navigate the complex and exhausting tunnels and curves of the inner lives of women: my daughters’ and my own. Jake keeps his own counsel. He is refreshingly transparent, but that is not to say he is one-dimensional. He has a remarkable sensitivity to music—to pitch, tempo, and song structure—which has been apparent in him since he was a toddler, when he would stand flailing at his plastic guitar in front of an armoire so he could hear the sound bounce off its surface. He is exceptionally even-tempered in a family with a lot of girls who incline toward the dramatic and convoluted in their emotional lives. He brought that with him when he was born—it was nothing I taught him. He has a dignity to his emotions that has inspired me to refine my own expression of feeling. In fact, I am certain I have become more circumspect about what I am willing to share with others because of his elegant example of judicious communication. I have to be careful not to make him a confidant or too close a friend; I remind myself that no matter how much apparent wisdom and self-regard he has in his emotional portfolio, he still needs a mother.

One day when he was four, he and I went to visit John at the recording studio on Gansevoort Street. When we left, it was bitterly cold. I couldn’t find his gloves, so I took mine off and put them on his hands. He looked up at me, confused. “But what about your hands?” he asked.

“It’s my job to take care of you right now,” I told him cheerfully. He looked down uncomfortably. I could tell he still felt uneasy and a little worried about my cold hands.

“Someday when I’m old and you’re a grown man, if I forget my gloves, you can lend me yours. Okay?” I smiled at him. He nodded, reassured, and we went on our way. My heart ached to witness his native compassion.

Although I was forty-three when I gave birth to Jake, I didn’t suffer unduly while carrying him or giving birth (except for a wicked and months-long postepidural headache, which turned out to be related to a then undiagnosed brain condition). It was, in fact, the perfect emotional age to have a baby. All the anxiety about balancing work and motherhood, about my own merits as a mother, about what was right for him, or right for me, dissipated. I knew what to do, and I was thrilled to do it. In a bittersweet way, losing the baby in the first year of my marriage to John enabled me to parent Jake from a context of pure gratitude. At his tenth birthday party, as I was setting up the balloons and the Lego party favors and the cupcakes, I overheard Hannah say to Chelsea, “Can you believe Mom is still doing the birthday cupcakes?” They shook their heads in sympathetic fatigue. I laughed. Thirty years of the birthday cupcakes. It’s a privilege.

I had begun recording a new album the summer of 1998, with John producing, and though we continued working as long as we could, we eventually shelved the project when it became clear that I could not sing at all. We picked up where we had left off after I began vocal work with Bill Riley. Although I had already written or cowritten eight out of the eleven songs I planned to record, I wanted to cast a net for some outside material, so preoccupied had I been first with trying to get pregnant and then with staying pregnant and feeling awful, and so frustrated at picking up the guitar when I couldn’t sing at all. We asked Craig Northey, from the Canadian band the Odds, and Joe Henry to contribute songs for the record. Craig sent “Beautiful Pain,” and Joe a song he cowrote with Jakob Dylan, “Hope Against Hope.” They were both great songs and a pleasure to sing, but the most fortuitous thing to come out of that commission was that I made two good friends in Craig and Joe. Joe and I have grown very close; he is a constant source of inspiration to me.

I had composed a chorus for a song called “Rules of Travel” years earlier, and though I had tried dozens of different melodies for the verses, I could never make it work; I could never even find exactly what I wanted to convey in the verses. Hearing me struggling with the song yet again, John finally said, “This is one of the best choruses you’ve written. You have to finish it.” We finished it together, and decided it would be the title of the album.

While driving on the Long Island Expressway a few years before, in a haze of anxiety about my dad, who was then suffering yet another health crisis, I had written the lyrics to “September

When It Comes” and put them in my purse. Eventually that piece of paper found its way to the third floor of our brownstone, where John picked it up. “What is this?” he asked. “This is really good.” He took the lyrics and wrote the melody, a mournful and exquisite piece of music.

I recorded “September When It Comes” when we came back to the project after the return of my voice. Listening to the completed track pensively, John observed, “You really should ask your dad to sing on this with you, as a duet.” I demurred, and when he brought the idea up again a few weeks later, again I declined. Several months passed and John said, “If ever there was a song or a time to do a duet with your father, this is the song and this is the time.” I suddenly knew he was right.

I called my dad and said, “Dad, I have this song, and I was wondering if you’d sing on it.”

He was silent for a moment and then said, “I’ll have to read the lyrics first.” I laughed and told him I’d deliver them in person.

I flew to Nashville with the lyrics and the audio files, and after reading the words to the song, he nodded. “I could do this,” he said quietly. He knew it was about his own mortality, about closing the door on the past, about what can never be resolved, only endured.

We went over to the cabin in the woods near his house, where he had his recording studio, accompanied by my brother, John Carter, who would record Dad’s vocal. Dad clearly wasn’t feeling well at all, so I gave him an out: “Dad, you don’t have to do this. We can do it another time.”

“No,” he said firmly. “I want to try it.”

As he learned the song, he got stronger with every take. I stood listening on the other side of the glass of the vocal booth, tears rolling down my face. We recorded three separate takes, and then he said, “You take that back to New York, and if John says it isn’t good enough, I’ll do it again.”

“It’s good enough, Dad,” I told him, laughing. “I promise you.”

When Al Gore spoke at Dad’s funeral on September 15, six months after the record was released, he mentioned the song in his eulogy and its strange prescience. “It’s September,” he intoned, and nodded at me.

When I was a child, I remember sitting in my fourth-grade Catholic school class and figuring out how old I would be at the turn of the century. It seemed unlikely to me then that I would live to be as old as forty-five at the dawn of the new millennium, not to mention absolutely inconceivable that I had a future as a middle-aged woman. I nonetheless placed those figures in my mental files and kept them there safely for years. In about 1998 I retrieved my childhood estimates and was startled to realize that my ten-year-old self had not allowed for the fact that I wouldn’t turn forty-five until May of that year, so I would actually be forty-four on January 1, 2000. I felt an unsettling ripple reach backward in time, to my fourth-grade classroom, freeing both my current and childhood selves. Having realized that I had been operating on a false premise for over thirty years, I now felt a palpable sense of relief. Maybe some of the other burdens I had carried from the past into my adult life had also been based on equally false assumptions, and maybe I could review some of them now, find a fatal flaw in my logic, revise my prospects for the future, make my way through my personal mazes, and put away some of my regrets and obsessions. It was never too late to undo who you had become.

My earliest memory, perhaps the earliest possible flawed template for my life, dates to when I was around two years old. We were visiting my mother’s parents in San Antonio, and my grandfather, Tom, the bespectacled insurance agent, master amateur magician, renowned rose breeder, and champion gin rummy player, took me to the park to feed the pigeons. He was sitting on a green bench, tossing seeds from a bag to the birds, which were flocking around his feet. He kept saying, “Look at the birds, Rosanne!” and I thought to myself, with a sharp clarity that I now spend most of my waking hours trying to recapture, Oh, I am supposed to pretend to be excited. I am supposed to act like a child. And so I did. I squealed obligingly, feigned alarm at the gathering birds, and pleased my grandfather. It was a bad way to start things off, actually—a compelling need to please people can be deadly.

In 1961, when we lived in Los Angeles, my father and I both suffered from respiratory problems. Even then, the air pollution there was significant, and that was why he’d decided to move us north to Casitas Springs, where the air was crystal clear and desert clean. I don’t think he even noticed how miserable the little town itself was, so pleased was he with the idea of owning his own small mountain, with absolute privacy and a desert climate. The only problem was that by the time he had the big ranch-style house built and moved us in, he was spiraling into his own extended experiment in chaos, self-destruction, and addiction, as well as constantly traveling.

Once, when I was about nine years old, my dad accidentally set fire to the mountain with a spark from the tractor he was riding. I called the fire department myself and said in the most adult and calm voice I could manage, “I just want you to know that Johnny Cash’s house is on fire.” The woman’s voice at the other end replied, very formally, “We’ve received the message.” For years I wondered whether she had given me the formal, scripted, official response to every report of a fire, or whether a dozen—or twenty, or fifty—people who lived down below in Casitas Springs, obviously delirious with excitement from the sight of the entire mountain in flames and the prospect of a celebrity’s house being consumed at any moment, had already notified the fire department, and the woman, weary from the flood of calls, had formulated a rote response that was short and to the point. I remember the feel of the smoke in my lungs that lingered for days afterward: the sensation of heaviness in my chest, the trouble and pain it caused me to take a breath. From my current perspective, with Mom and Dad dead and my sisters scattered to every far corner of the country and everyone who’d ever lived in Casitas Springs in the 1960s surely dead or relocated, I think that if I had had the presence of mind as a nine-year-old, I would have told Dad to just finish the job, burn the whole mountain, and save us all a lot of unnecessary psychic torment on that lonely, arid, snake-infested hillside.

In 1979, I checked my guitar, a Martin D-28, at the curb at LAX on my way to Hawaii to begin my honeymoon with Rodney, which had been delayed for three weeks while I was finishing my first album for Columbia. I waited at the little outdoor baggage claim in Lihue for my guitar to come off the carousel, but it never did. Rodney became alarmed even earlier than I did, and began saying, “I don’t think your guitar is going to show up.” Even when it was clear that it was missing, even after we had filed the missing luggage report, I still felt fairly confident that it would appear. Thirty-six years later, I am still waiting for that guitar to turn up. It had been a gift from my dad, who had inserted a handwritten note into its sound hole saying something to the effect that it was a present from him to me, his daughter, with love, along with the date.

Somewhere, someone has my guitar and knows damn well it belongs to me. Since the advent of the Internet, I have made halfhearted attempts to find it. I have alerted my friend Matt Umanov, of the legendary eponymous guitar store in Greenwich Village, to the style, color, and year of the instrument, and he has promised to keep a lookout. I have an illogical but certain belief that my guitar will be returned to me before I die, even if I am ninety years old and have only a week to live. I just know I will see that guitar again. I am counting on it. If my dad, from his perch in the other world, wanted to do something really great for me, he might hasten its return. I’m sure he knows where it is by now.

I went to so many funerals over the course of six months in 2003 that I eventually developed a relationship with the directors of the funeral home in Hendersonville, Tennessee, where my father, my stepmother, my stepsister, and my aunt were dressed and laid out before they were buried in the cemetery right across the parking lot. I spent a lot of time in those offices, making decisions with my siblings about the color of caskets, the wording of obituaries, the size of headstones. Weight of hea

rt. Look of future. Lack of answers.

One horrible day in a long string of horrible, macabre days that year, while I was walking down the wide hall between the individual “parlors” of the funeral home, one of the directors stopped me to inquire about my own plans for the disposition of my body after my demise, and whether they might “take care of me,” since they now had such an enduring professional relationship with my entire family.

“No, thank you,” I replied, shuddering. “I’m not going into the ground. I want to be cremated.”

He became instantly alert and focused. “Would you like to be a diamond?”

“Excuse me?”

“There’s a lot of new technology. You can have your body reduced to carbon and turned into a diamond.”

I paused. “Let me ask my daughters if one of them would be interested in wearing me around her neck, and I’ll let you know.”

At June’s funeral I wore a black Jil Sander suit with a knee-length skirt and collarless jacket, one of the most expensive items of clothing I had ever purchased. I had bought it a few months earlier under the assumption that I would be wearing it to my dad’s funeral, as he was back in the hospital and we were all frantic with worry. Dad recovered, so I wore the suit, along with black satin Prada shoes and a black satin wide-brimmed hat, to bury June.

I carried one of her old handbags as I delivered her eulogy in the cavernous modern Baptist church in Hendersonville:Many years ago, I was sitting with June in the living room at home, and the phone rang. She picked it up and started talking to someone, and after several minutes I wandered off to another room, as it seemed she was deep in conversation. I came back ten or fifteen minutes later, and she was still completely engrossed. I was sitting in the kitchen when she finally hung up, a good twenty minutes later. She had a big smile on her face, and she said, “I just had the nicest conversation,” and she started telling me about this other woman’s life, her children, that she had just lost her father, where she lived, and on and on. . . . I said, “Well, June, who was it?” and she said, “Why, honey, it was a wrong number.”

Composed

Composed