- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

Composed Page 2

Composed Read online

Page 2

I ultimately developed a near-psychotic phobia about snakes, which resonates in me even now. After those years of forced rattlesnake immersion, when we left the mountainside I saw only one more snake in my entire childhood: a pet king snake that the boy next door brought over so he could tease me. He didn’t anticipate, nor did I, the effect it would have on me, and he stood openmouthed in disbelief as I jumped up onto a table, screaming and crying in hysteria at the sight of it. He looked thoughtful for a moment, then quietly turned around and took it back to his own home. I never again saw a snake, or even mentioned the word, until I moved out at the age of eighteen.

The other menaces on our land (besides the drunken folk singers who regularly wandered to our door looking for salvation and inspiration in the person of Johnny Cash) were giant poisonous desert arachnids, which I would trap in mayonnaise jars as my own private science lab and spider jail. I experimented with them, feeding them and not feeding them, letting them have oxygen and not letting them have oxygen, to see how long they would survive. I had no mercy. A scorpion or a tarantula was a nasty thing to find in your bedroom, and one could easily bite my little sister as she was toddling in the yard, or our mother’s Chihuahua. One of them did bite our German shepherd, causing his face to swell horribly. I remember my dad’s pity for the dog, and the dog’s oblivious expression as he walked around with his face almost double in size. My dad explained that the dog had been bitten on the head, and I corrected him, silently, to myself. Not the head. The face. I felt a great sense of power when I entrapped a giant tarantula in a large jar and put my face close to the glass, where it could do nothing to hurt me.

The Chihuahua, for her part, escaped any such attack, but gave birth to four puppies, all of whom died at birth because their poor little slip of a mother had whelped too many at once. My dad put them in a shoebox and set them on the low-overhanging shingled roof at the end of the house, near the outdoor stairs that led to the cookout area. I have no idea why he didn’t bury them in the ground. He might have been in his Native American obsessive phase and wanted to give the puppies a Choctaw burial on a scaffold. Perhaps he wrapped fancy little blankets and sacred beads around them as well. Every time I walked past that end of the house, I eyed the roof nervously. I couldn’t see the box, but I knew it was there, full of dead puppies decaying under the sun. I don’t really remember what happened to the mother dog. She just had too many babies, and there is no remedy for the body when it is too small and required to do more than it can manage.

Years later, when I had my first child at the age of twenty-four, I lived in similar mountainous terrain in a rambling house in Malibu Canyon. One morning I looked across the room at my seven-month-old baby crawling across the den, and then I spotted the scorpion she was pulling herself toward, thinking it was some kind of strange toy. It was at that moment, I think, that I began to become a New Yorker. I wanted nothing more to do with desert arachnids, venomous snakes, or brush so dry it would ignite just from the sun.

Our home in Casitas Springs was a large ranch-style adobe and shingled house with a small backyard and a huge asphalt driveway and turnaround where I spent many hours riding my bike. The home site stood on the side of a brush- and cactus-covered mountain, about halfway to the top, and overlooked the dismal lower-middle-class community a quarter mile below. My father had bought the land, cut into the side of the mountain to create a level area on which to have his rough castle built, deposited me, my mother, and my three sisters there, and then went on the road for a decade.

Every couple of weeks someone—the previously mentioned folk singers, as well as addicts, preachers, or the occasional sex kitten—would drive up the long road to the house, usually late at night, usually drunk, looking for Johnny Cash. “He’s not here!” my mother would shout, slamming the door on them.

We liked driving people away. We had a series of live-in house-keepers, one of whom quit the second day on the job because dinner had to be served at nine p.m. the night before due to unexpected guests. She left a note on the door to her room, a small apartment with a separate entrance attached to the house, explaining that she simply could not live with such erratic schedules and late meal-times. It was probably the only time in my childhood that dinner had been delayed until that hour, but no matter. Good riddance to those who might intuit the strangeness. The only people I genuinely welcomed were those who performed services for us and then left—the carpet cleaner, the milkman, the Helms Bakery man, the gardener, and the Jewel-T delivery man, who brought a combination of snacks and household products. My mother had everything delivered, a practice I have since refined immeasurably as a New Yorker.

At five foot four and ninety-eight pounds, my mother was a small, nervous slip of a woman who lived on Winston cigarettes and coffee. She was deeply distracted by worry and rage about my father, who was not only constantly traveling, but also unfaithful and at the time using massive amounts of amphetamines and barbiturates. She eventually became so fragile and distant from us children, from her pain over her failing marriage, that I, as the oldest daughter, began to assume more of an adult role in the family. I was the fourth player at cards when couples came to visit her. I was the one my sisters turned to in times of trouble. I was the one who had to pretend not to be a child. I began to hate the very word “child,” which seemed almost shameful—I remember how awkward it felt in my mouth and the unease it provoked to say it or hear it spoken. As if my mind could not reconcile with my age and my body, I began to have dreams that seemed frighteningly prescient, and visions that disturbed me.

I would often go into my parents’ bedroom to look at my mother’s clothes. She had a cocktail dress with a gold lamé bodice and a beige chiffon skirt, which I coveted with all my heart. I would open the long, mirrored sliding door to her closet and gaze at that dress until I’d memorized every detail of its appearance and texture. This is what real women wear, I thought, and I knew, as I fingered it longingly, that I would never own such a dress, because I would never be a real woman like my mother—because I would never smoke cigarettes or drink coffee, both of which repulsed me, and I was going to be five foot five and a half, and well over ninety-eight pounds: bigger than she, which was in poor taste and therefore unwomanly. I realized with absolute and sudden clarity one day while fondling the cocktail dress that if my life was going to be like this—not only being the fake girl, but now also being the fake adult when I was only eleven years old—that I did not wish to wear ankle socks anymore. The least everyone could do was to give me a pair of proper stockings and a garter belt. If I couldn’t have the dress, I could at least have the undergarments that went with it.

I never cried, a fact in which I took great pride. But if nothing could reduce me to tears, everything had the potential to reduce me. My shoes and the feet inside of them reduced me to a paralysis of confidence. A broken zipper reduced me to eating baby cereal furtively, sitting alone in front of cartoons, at the ages of ten and eleven. Dead puppies reduced my future to a pinpoint. A scythe, which I swung wildly but to absolutely no effect at the waist-high weeds up by the cookout area near the built-in picnic table, reduced my forearm by a centimeter of skin, the scar of which I bear to this day.

My mother insisted on certain nightly rituals, which were as unyielding as gravity. I had to curl my hair on pink foam rollers and I had to polish my shoes, a task I carried out with a numb, unfocused displeasure that grew into an acrid background fog that permeated my entire life. I had, as it happened, a problem with my feet. They were too big, bigger than my mother’s—size 8½ to her delicate size 7 by the time I was twelve—and I was constantly injuring them. They were stung by bees and swelled up like balloons; they were smashed under overturned piano stools; they were cut by open sardine cans at the park; they demolished tiny things that came into their path. Everything about them was further evidence of my not being a real girl. My mother did not help matters by pointing out their defects, which I interpreted as meaning that no one would ever mar

ry me. She also did not help by insisting that I wear oxfords—part of the school uniform—that were all white, rather than the much cooler black and white, which most of the other girls had. The whiteness of the shoes only accentuated the great length of my feet.

The other problem was my body, which in retrospect I think of as an adorable butterball but which at the time seemed like a corpulent rebuke to my mother. I famously broke the zipper on my mother’s wedding gown when I tried it on at the age of ten, a story she took great pleasure in repeating for many years. She was very proud of her own ninety-eight pounds. Almost four decades later, I took her to meet her surgeon two weeks after she was diagnosed with lung cancer and two weeks before she died, following the surgery. She sat in the examining room on the white-papered table and listened as he carefully described the surgical procedure he would perform on her. At the end of his speech, she said, nervously and only half joking, “And can you do something about this fat while you’re in there?” By then she weighed about 140 pounds and was still perfectly beautiful.

When I was twelve, my parents finally split. My father was by then involved with June Carter, and my mother was with Dick Distin. Shortly after the divorce became final, they each married their new partners. My father was by now living in Tennessee, and my mother, Dick, and my sisters and I moved to Ventura, to another house on the hill overlooking the ocean. That house was a sixties fantasy come to life—a low-slung, single-story ranch with natural stone and rock accents. It had a tiny outdoor area and an enormous indoor pool area with hot pink furniture and awnings. A beaded curtain separated the sunken living room from the rest of the house. The den featured a wall made of boulders with a built-in oven, and my mother and Dick had a round bed in the master bedroom. My mother let me meet with an interior designer to select the colors and fabrics for my own bedroom, which had a sliding glass door leading to the pool area. I chose a lime green and royal blue palette, with a large floral print for the curtains and bedspread. The house was written up in the style section of the Ventura Star-Free Press, with several photos—including one of me in a bikini sitting by our indoor pool with the pink trimmings, looking, perhaps, a bit too self-consciously bemused.

It was as if, with that move, someone had opened all the windows and let the light and air inside. My mother almost immediately flourished, making a lot of friends, joining a garden club and a bowling league, taking dance lessons, playing card games, and hosting memorable parties. She crocheted, painted, gardened, renovated, organized, and collected. She became deeply involved in her church, and became close to many priests and nuns. She was vibrant. Because all my own friends loved her, a sizable group of teenagers inevitably gathered at our house. My mother remained in touch with two of my closest friends from high school until her death. They called her Viv. My dad had gotten clean and sober, and had bought an enormous, rough-hewn house of wood and stone perched on a bank of Old Hickory Lake in Hendersonville, twenty miles north of Nashville. Beginning when I was twelve, the summer after the divorce, my sisters and I began spending six weeks of the summer with him in Tennessee, as well as two weeks at Christmas break and the odd weekend when he would pick us up to take us on the road. He was physically a wreck that first summer, gaunt and hollow eyed, but by the next one he was whole and healthy and gaining weight.

Those summers of my early teens were glorious. Dad taught all of us to water-ski, and we swam in his giant rock pool that fed into the lake, and we went on long jeep rides at his farm in Bon Aqua, seventy miles from the lake house. We picked wild blackberries and he played guitar and we sang in the evenings. Out on the lawn after the sun went down, he made homemade peach ice cream with peaches from his orchard, setting off firecrackers while he cranked the ice cream maker. He cranked that old silver tub for an hour or more, but he never complained. He picked up all the kids in the extended family—June’s sisters Helen’s and Anita’s kids, and various other children in the neighborhood—and took us to the movies when it was too hot to play outside. Sometimes he took us to three movies in a day. He rented the roller skating rink so we could skate together, undisturbed by fans.

By the summer of 1968, when I was thirteen, June and her two daughters, Carlene and Rosey, had moved in; June and my dad had married that March. One day I heard Carlene refer to my dad as “father.” My hackles went up. She had her own father. He was my father. I said, “When did you start calling him that?” and I made it clear I didn’t like it. She demurred and never called him father again.

By my mid-teens I was having summer flirtations with the sons of the accountants and musicians. I was going to dance clubs and swim parties and sometimes sitting in on Carlene’s classes at Hendersonville High School when she started there in August, before I went back to California. I thought the kids my age in Tennessee were rubes, in general. I considered myself musically and stylistically sophisticated, refined by Woodstock-era and Southern California sensibilities, while they all seemed to be about a decade behind—I didn’t know if they had even heard of Woodstock. I looked different, too. I was wearing bell-bottoms and had long, straight hair while most of the girls there were still in curls and skirts. Carlene, though, had a wild streak that didn’t jibe with her Southern façade. The summer we were fourteen, she borrowed Bob Wootton’s Harley-Davidson motorcycle, and I got on the back and we rode around the lake. The bike was so heavy that two small fourteen-year-old girls couldn’t hold it up, so we just kept moving. We didn’t stop anywhere, including intersections. My dad never knew we had taken the bike. He would have killed Bob.

Dad didn’t tour when it was our summer vacation time with him. I didn’t realize until much later how lucrative the summer touring was that he gave up to teach us to water-ski and make ice cream. He had signed a statement of promise when he married my mother saying that he would cooperate in raising their children as Catholics, and my mother was absolutely unwavering about this. He dutifully took us to Mass on Sundays and sat with us in the church, silent, never judging, never saying a word. When I was about fifteen, I finally told him I had no interest in going to Mass and I begged him not to make me go anymore. He looked at me with some surprise. I said I wouldn’t tell my mother. I could see this caused him a moral dilemma, but by the time I was sixteen, he’d relented. I didn’t have to go to Mass anymore. He said that at sixteen I was old enough to make my own decision. He continued to take my sisters for a while longer. I felt a little guilty about not going to church at all, having never missed Mass for my entire life, so I experimented with Southern Baptist and Evangelical religion for a short time, thinking I would try exactly what my mother most judged and feared, and something closer to my dad’s heart and upbringing, but that didn’t turn out well for me. I didn’t like the lack of dignity and personal boundaries in the free-for-all shouting and preaching and laying on of hands, and I realized I enjoyed the rituals of religion far more than the substance. I was more Catholic by nature than I had known. Interestingly, my dad didn’t go in for the overt emotionalism of his own religion, either. He had powerful religious beliefs, but he seldom went to church.

When I was sixteen, he took Kathy and Rosey and me to Europe with him, my first trip abroad. We visited Anne Frank’s house in Amsterdam, which made an indelible imprint. I found I was more a natural traveler than anything else, and that trip began a lifelong series of sojourns to Europe, and more generally a life circumscribed by travel.

It was during this period that a great, gray fog seemed to lift from my family for a few years. My dad was at a peak of success and health. He was gaining in physical and artistic power, and his television show was a huge hit. After Bob Dylan or Joni Mitchell or any of the icons of my youth were guests on his show, I went to school the next day bursting with confidence and pride. I basked in that reflected glory. Both of my parents were flush with romance and exuberance in their new marriages, and I was feeling the first stirrings of my own independence. I went to high school at St. Bonaventure in Ventura and wore my Catholic uniform skirt ve

ry short. I had my first boyfriend, and I fell in with a small group of classmates who were a little left of center, like me. We called ourselves the “Anarchy Society.” The Anarchists managed to wield enough power and votes to elect me senior princess for homecoming, to great consternation and protest from the “rah-rahs.” My dad got me tickets to see the Rolling Stones in Los Angeles and he bought me a car. I briefly fell in with a surfer crowd, although I never fit in with them. I began to nurture magnificent surges of melancholy and longing, which I attempted to turn into bad poetry. I finally began to break loose from the internal pressure of religious and domestic constriction, and to understand what I loved and who I might become.

If Magritte had painted my childhood, it would be a chaos of floating snakes, white oxfords, dead Chihuahuas, and pink hair rollers. Bolts of gold lamé and chiffon would be draped over everything, stained with coffee and burned with cigarettes, and garden hoes would be wielded by drunks with guitars. Glass jars full of spiders and amphetamines would line the walls behind the sliding mirrored doors. The landscape would be barren and steep and full of animal treachery. There is nothing green. There is no oxygen. I am a foreigner in this painting. I look at it as if in a museum. I can talk about the color of the oils and the depth of field, how the two dimensions feel like three when I know there are four, but I cannot be a line drawing or even an abstract smudge in the center and survive to describe it.

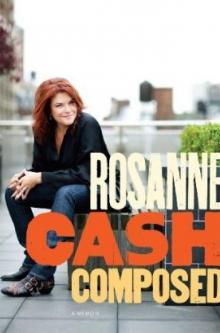

Composed

Composed