- Home

- Cash, Rosanne

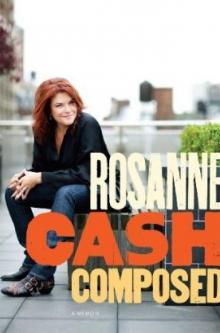

Composed Page 18

Composed Read online

Page 18

It had nearly frightened, but hadn’t surprised, me how much my father was there the night of the Oslo prison concert. Of course he never heard it, never knew it took place, never saw the yellow lights that dropped like giant egg yolks on the cobblestones, never walked through the icy fog into a roomful of facsimiles of himself. And yet there he was, liberated from the small pins of hurt and regret that had stayed lodged in his heart, released from the wrecked cars, the ravaged old/young body, and the grown children who needed assurance in the most unlikely places. I think he was finally comfortable with the tears at Oslo prison, and at Falkland Palace, perhaps even reveled in them with love and permanent detachment, as a man can do when he knows he is not responsible anymore.

On November 27, 2007, I got up at five a.m. and took a shower. After dressing in a blue-and-white-striped Comme des Garçons man-style shirt, black trousers, and black satin ballet slippers, I went down to the kitchen, where John, Chelsea, and my sister Tara were waiting for me with controlled, unnaturally calm expressions and superficial cheeriness. I was having none of it and instead started singing softly, “If I only had a brain . . .”

“Mom, STOP!” my daughter said with annoyance.

I asked my sister to take my picture with my cell phone. I look at that photo today and can’t believe how bad I looked.

We got in the car and drove up the West Side Highway to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital at the northern tip of Manhattan. I put my headphones on for part of the drive so I could listen to my “preparation for surgery” relaxation tape, which Nolan Baer, a talented hypnotherapist and friend, had made for me. After checking into the hospital, I was sent to a holding room on another floor, which reminded me of a backstage greenroom but with a lot of scary equipment and no refreshments. As my small entourage stepped through the door, a woman seated at a nearby desk warned crankily, “Only two other people.”

I looked at my sister and my daughter. “Both of you go upstairs,” I said. “It will be easier if just John is here.” We hugged quickly and they left.

As I put on a hospital gown, I felt my stomach begin to churn and asked for a Valium. I went to the bathroom, twice, but nothing was happening. Back in the holding room I perched on a gurney in my personal little cubicle—one of several little cubicles arranged in a semicircle around a lot of carts and shelves and busy nurses in the center of the room—and took my husband’s hand. After a few minutes, a tiny, lovely dark-haired nurse came to officially check me in. She said hello and looked at my chart. Although she knew full well why I was there, she asked sweetly, “And what are you here for?”

“Liposuction,” I replied without a smile.

Her eyes grew wide, and she froze. I could see her mentally running through the list of possible consequences of her misunderstanding: disciplinary board hearings, lawsuits, job loss . . .

“Stop torturing her,” my husband said gently.

“I’m here for brain surgery,” I said and this time smiled.

“Whew,” she said, smiling in return. “Okay. Can you explain it? Can you tell me exactly what kind of brain surgery?” she asked, pen poised above my chart.

She certainly didn’t need me to explain it, but there must have been a check to mark beside a notation that read “Patient fully understands nature of procedure.” I mused for a moment. Brain surgery covers a wide range of possible events, from the drama of snipping giant aneurysms to brain mapping of a conscious patient for epilepsy, from the minor surgery of drilling tiny holes and placing shunts to relieve spinal fluid to—to my case.

“I’m having a decompression craniectomy and laminectomy for Chiari 1 and syringomyelia,” I said in a self-confident rush, having researched these terms so thoroughly over the past three months that they now rolled off my tongue as easily as “verse, chorus, bridge.” In other words, a brain surgeon was going to take a Midas Rex drill, saw open the back of my head, remove a credit card-sized portion of my skull, cut through the lining of my brain, break my top vertebra, free my entrapped cerebellum and release the dam of spinal fluid, close the hole in my skull with a Gore-Tex patch, and then staple my head together, straight down the back, like a big zipper.

I somehow always knew that I would have brain surgery. From childhood, it seemed like a familiar experience, and something that didn’t unduly frighten me. (That’s not entirely true—it frightened me terribly, but it didn’t seem out of the realm of normal potential life experiences.) I am not sure why, but I do know that when I was advised by five different neurosurgeons to have brain surgery, and not to take too long in getting it done, it seemed like a foregone conclusion, a foretold event.

I had had debilitating headaches for twelve years prior to my diagnosis. My neurologist was a migraine specialist and saw everything through the lens of his own specialty, as many doctors do. First he told me I had migraines. Then, when some of the headaches didn’t follow a predictable model, he said I had “atypical” migraines. Then, when the atypical migraines became part of a laundry list of other symptoms that were difficult to parse, he told me I had migraines complicated by hormonal changes and stress, the catchall diagnosis for women in middle age. I became desperate for help. The headaches were happening every day. I had to quit yoga, which I had done for over a decade and which I loved, because my spine hurt and my neck was in constant spasm. I had been hit by a couple of “thunderclap” headaches in yoga class—which feel like being struck by lightning, hence the name—and I was leery of going back. I was also losing my stamina. I had been a workhorse; no schedule had ever been too daunting for me, but I was beginning to tire after just a single flight or a single show, something that had never happened before, even with the headaches. I had a few MRIs and was told there was nothing significant or troubling.

By the summer of 2007, I was in constant pain, had suffered a series of high fevers and infections, and was constantly exhausted. In August I decided to change neurologists, and went to see Dr. Norman Latov at Cornell. Within two weeks, after a series of new scans, he diagnosed me .

“I can’t help you with this, and there are only a few neurosurgeons in the city who I would trust with this,” he said as he began to write out referrals.

“Neurosurgeons? Is it a tumor?” I asked. I felt very calm, even relieved.

“No, not at all,” he said. Then he told me he had seen only two people with my condition in his professional life, but he was confident I could get better.

“What did he say?” John asked when I called him after leaving the office.

“My cerebellum is too low, and it’s crushing my brain stem,” I told him, using this new vocabulary with unexpected confidence. “It’s creating a dam. I have only a trickle of spinal fluid going into my head, and I have a swelling—something called a syrinx—in my spine, from the pressure of the fluid not being able to get up into my brain.” I paused. “How do you feel about brain surgery?” I was trying to be casual, so I wouldn’t upset John unduly, and also to inure myself against the shock by saying it aloud.

John, as is his nature, took this news calmly and reasonably, and immediately tracked down the top five neurosurgeons in the country.

We sent my scans around the country and arranged phone consultations with a doctor at Johns Hopkins, one at UCLA, and the head of neurosurgery at the University of Wisconsin (a colleague of John’s brother-in-law), and had appointments with two others in New York City. All five said the same thing, basically, although one put it particularly succinctly: “That little trickle of fluid you have in your head? That’s what’s keeping you alive.”

We eventually chose Dr. Guy McKhann II—a kind young neurosurgeon and himself the son of the neurologist we had consulted with at Johns Hopkins—at Columbia Presbyterian to do the surgery that had been prescribed. He encouraged me to prepare myself mentally, as it was going to be a tough ordeal. That was an understatement.

The hardest part of the three months between my diagnosis and the surgery was the time I woke in the middle of the night to

find John leaning over me, his tears falling on my face. He was the most perfect patient advocate anyone could hope for. He was a rock and a defender and a guide, and only that one night, when he thought I was asleep, did it ever become too much for him.

Dr. McKhann, who would soon be making his way into my head, now approached me with a team of even younger doctors flanking him on either side. “How are you doing?” he asked as genially as the intake nurse had.

“Just great,” I replied. “But how did you sleep last night?” I asked anxiously, trying to put aside visions of a sleepy, shaky neurosurgeon doing any of the procedures I had been imagining so obsessively.

“Perfect,” he said.

“And have you read Jimmy Breslin’s book on brain surgery?” I asked. (I had devoured a few books about neurosurgery in preparation for my own: the great novel Saturday by Ian McEwan, When the Air Hits Your Brain by Frank Vertosick, and Jimmy Breslin’s account of his surgery for a dangerous aneurysm, I Want to Thank My Brain for Remembering Me. Breslin’s account was written in his characteristic old-school newspaperman’s clipped tones, and I had found it both charming and compelling.)

Dr. McKhann looked bemused. “No, should I?”

“Stop it,” John said again gently.

My anesthesiologist, Dr. Eric Heyer, sauntered up. I suspected—and hoped—that he had a wicked sense of humor, which I thought I had glimpsed in our consultations up to this point. I had total confidence in his ability to keep me deeply unconscious—“below the level at which the brain can imprint memory”—and immobile during surgery, but I was also counting on his wit to help me get through the next half hour, while I was still awake and anxious. I looked at him eagerly.

“Have they given you the Valium yet?” he asked.

“No,” I said, perhaps a bit more forlornly than I intended.

He stepped over to the nurse’s station and found one for me and held it out in his palm. I took it and swallowed it gratefully.

“Okay!” he said as jauntily as if we were headed for a pleasant Sunday drive in the country. “Let’s go!”

“I was hoping it would have time to work first,” I grumbled faintly as I got off the gurney.

Dr. McKhann said he would see me later. I hugged John quickly—refusing to give space for any excess melodrama to arise—and told Dr. Heyer I didn’t want to be wheeled into the operating room. I explained that I would be more frightened if I didn’t step into it under my own steam.

“Fine with me,” he said, and Dr. Heyer and I walked to the operating room together. Just as we pushed through the big double doors, he leaned over and whispered to me, “I’ve done this twice before, and it turned out well both times!”

I entered laughing, took a wary look at the array of computers they were going to hook up to my brain, and climbed up onto the table. A very young resident, one of the team who would be rearranging the map of my brain, was beside the table, wearing Buddhist mala beads around his neck. He smiled at me. I suddenly felt more relaxed. Then an adorable senior resident in a Russian skullcap stuck a needle in my arm, and just when I was about to start flirting with him, I drifted into unconsciousness and the day went by.

Six hours later, the first words I heard were Dr. McKhann’s, asking me if I knew where I was. I opened my eyes. I was still in the OR, but the color of the walls was similar to that of my kitchen.

“I’m in my kitchen,” I mumbled. I heard him laugh.

“No, you’re not in your kitchen,” he said. I closed my eyes.

“Yes I am,” I insisted drowsily.

Then I saw John’s smiling face hovering over me, and I smiled back as reassuringly as I could manage, to let him know I wasn’t brain-damaged and that he could stop worrying. When I awoke again, I was in the neurological ICU and had the most unbelievable headache, one that made the pain of childbirth seem like a routine dental cleaning. That particular headache would last, I would soon discover, for a few months.

I was pumped so full of steroids and morphine that first week that I recall very little in specific detail. I do remember the pain. I also remember that my special black tea, which I had brought from home, tasted completely different than it normally did, and I remember how frustrated I was that something as simple and familiar as a cup of tea didn’t provide the usual comfort and satisfaction. I remember walking for the first time, two days after the surgery, and the effort it required to remember how to step up a single stair. John practiced with me. “First you put one foot on the stair,” he urged, “then you lift your body and then the other foot . . .”—instructions that seemed so hopelessly confusing that I struggled to understand the sequence. “Why can’t you do this?” John asked calmly, staring at me. There was no fear in his tone of voice that I might be damaged, no frustration, just a simple question that I could ask myself: “Why can’t I do this?” Until I could.

I remember the residents, who checked in on me several times a day, and how sweet they were, particularly the one wearing the mala beads. He had a special gift for healing just with his presence. I remember the pain service doctor, who carried a full syringe of morphine in his pocket and whom I actually pulled down to me and kissed once, in utter gratitude. (He blushed but seemed flattered.) The photos my sister took during my hospital stay reveal that I had a spectacular view of the Hudson River from my room in the McKeen Pavilion, but really, it was wasted on me. I remember crying when I was alone at night, while watching Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible. I remember eight-year-old Jake coming to visit, and trying to test him on his spelling as he lay next to me in the hospital bed. “Mom! ” he reprimanded me, after a couple of words. “You’re falling asleep!”

Six days later, they sent me home. John didn’t tell Jake he was bringing me home that day. He got me settled in bed, and then brought Jake into the bedroom to surprise him. His little face melted with relief when he saw me and tears filled his eyes. I suddenly realized the depth of the stress and worry he had been carrying, and keeping to himself. He climbed onto the bed and I hugged him tightly.

I had nineteen staples up the back of my head. I learned there was a community of people who had my condition and had gone through the same surgery, who called themselves zipperheads. I was mildly amused, and enjoyed referring to myself that way on occasion, but I adamantly refused to join any community that identified itself by an illness. The idea of becoming a spokesperson for this condition, which I was asked to do before the staples were even out of my head, was appalling to me, and entirely against my nature and sense of privacy—I was not inclined to trade publicly on anything relating to my health or my body, even, unfortunately, in the service of others who suffered with the same disease. The recovery was hard, harder than I imagined. I think I expected just to have headaches, but that kind of surgery is a total body event. I was traumatized, weak, and everything hurt—not just my head. Before the surgery, I foolishly thought in three months I would be better, so I had planned to resume performing, and the first dates on the calendar were in mid-March. I went to Florida to play a show, and the flight alone set me back by weeks. I regrouped. This was just going to take a lot longer than I had anticipated, and I would readjust my planned trajectory back to health.

My friends, particularly my girlfriends, were phenomenal. Every day for the first few weeks, someone would come by to sit and watch a Bette Davis movie with me, or drop off a casserole for John and the kids, or just sit quietly next to me on the bed when I was too miserable to talk or listen. Chantal Bacon, my next-door neighbor and one of my dearest friends, visited many times just to make tea for me, as she knew exactly how I liked it. She would brew a pot, arrange it on a tray, smile, and almost imperceptibly leave. My friends Gael Towey and Stephen Doyle made applesauce for me a few times, and it became the only thing I wanted to eat. Stephen ferried it over to me on his bicycle. Chelsea went back and forth to Nashville, where she was living, to help with Jake and the house, and calm Carrie’s nerves about me.

John read aloud to me Che

khov’s “The Bet,” and in my morphine haze the images and language became almost surreal, and wonderful. That was perhaps the best moment in my early recovery.

Because of the slow pace of recovery, I was frustrated and even despairing at times. I went deep into my pain, ascribing all kinds of portentous meaning to it. The changes in barometric pressure that accompanied an approaching storm laid me out on the sofa, immobile, with a crushing headache. They had broken my top vertebra during surgery, intentionally, so they could free up the trapped cerebellum, and my neck felt like a concrete brick. It hurt constantly. My left ear developed overly acute hearing, and I found that I couldn’t bear not only noise but any music with lyrics—the words seemed too complicated, and irritating. I listened to classical music in those first few months, and nothing else. Mostly I wanted silence. I was enormously sensitive to sensory overload, and I stayed inside my house most of the time to avoid sounds of traffic and sirens, loud voices, and dogs barking. Sometimes I reversed words when I was talking, or replaced common words with others that weren’t even close in meaning. My friends laughed when that happened and told me it was adorable, that I shouldn’t worry about it.

In my self-pity I went so far as to convince myself that both my parents had somehow known I was going to have brain surgery and had decided to die before it happened so they wouldn’t have to go through the agony of seeing their child undergo such a terrific ordeal. This little exercise in morbid narcissism allowed me to become furious with them, and feel justified. Then, at some point, that all dissipated and I was glad—more than glad, I was deeply relieved—that they weren’t around to witness it, as I knew how much it would have taken out of both of them. My brother came up to New York from his home in Tennessee, and my sister from her home in Port-land, Oregon, to offer comfort in lieu of our parents. I was grateful for that.

Composed

Composed